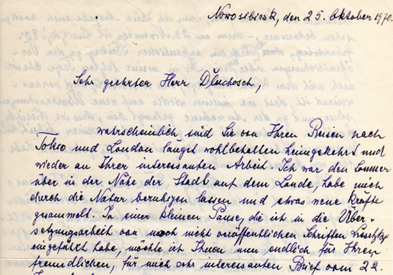

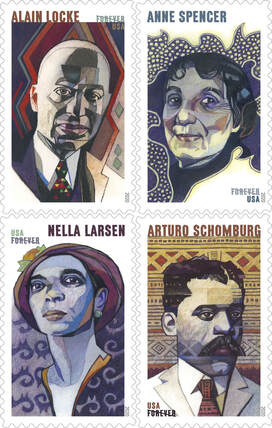

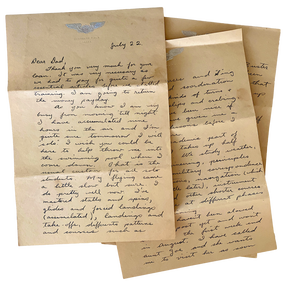

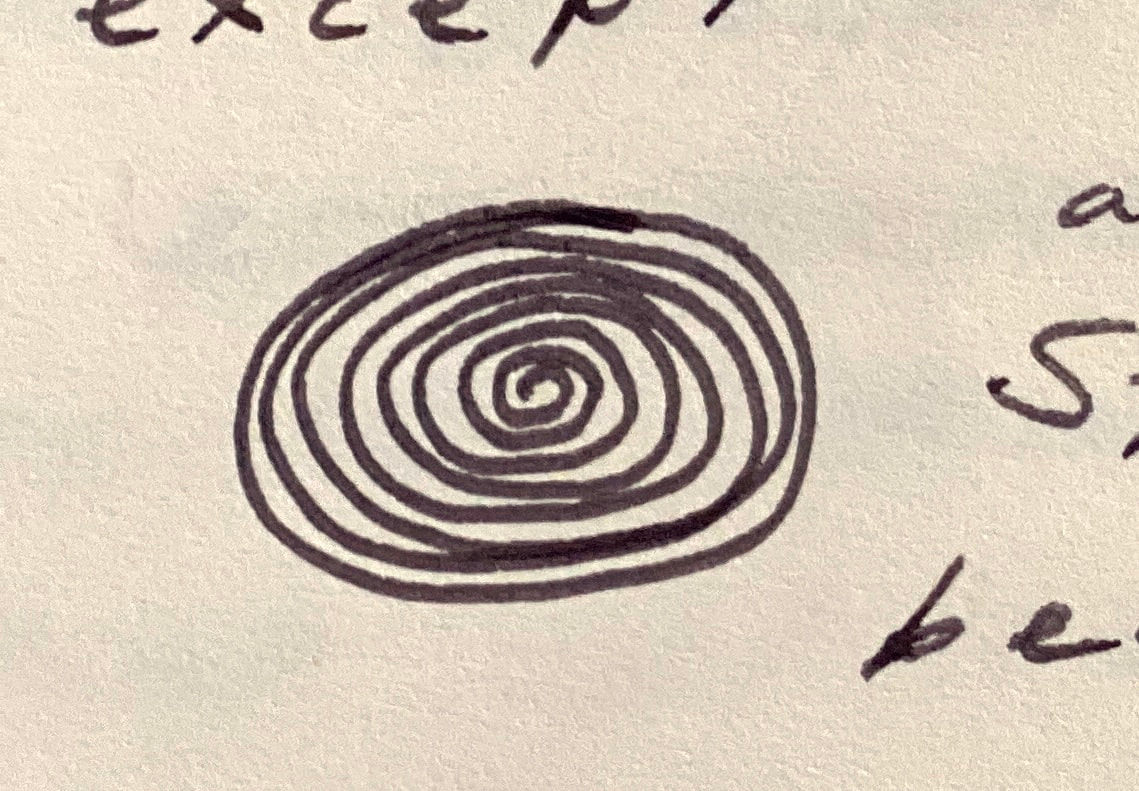

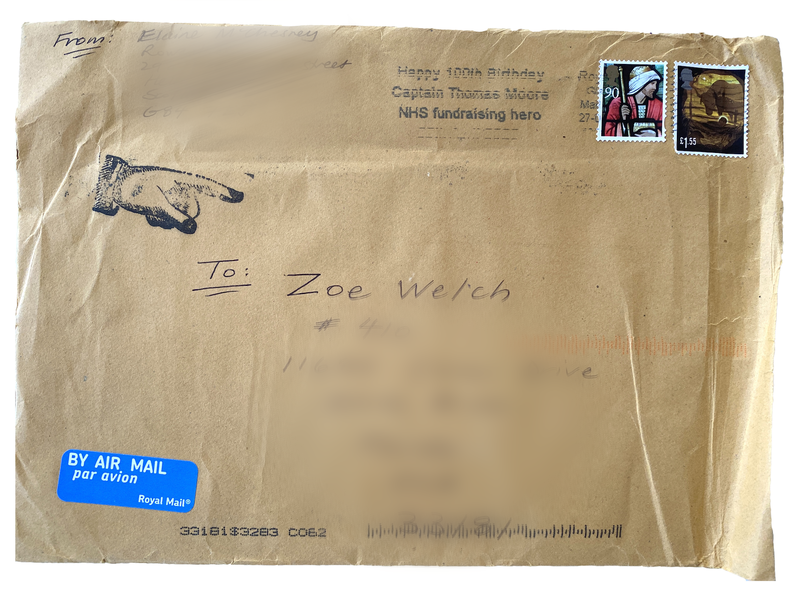

(For E. a letter-writer.) Don’t you want to pick that up? Turn the sheet over in your hands, hold it up to the light and see the glow through the page, feel the texture of the ink on the paper, sense the sender and the sendee, feel yourself carried through time to where this was, almost becoming the script, the scribe, and the go-between. I want to.  It looks like it's written on onionskin paper—a virtually sheer sheet, its lightness important during the days when airmail (called Par Avion at its inception in London in 1929) was costly and people economized on postage by using lightweight paper. I don’t know if I would be as inclined to want to handle and explore this letter if it were typewritten, to let it linger in my hands, its physicality the thing transmitting the fullness of its metaphysical dimensions. I might still want to read it as eagerly, but with so much sensorial promise gone, much of the personal would be too. Letter-writing gets short shrift these days, considered a relic at best, a waste of time at worst; it’s gone from something quintessential to something antiquated, something once consequential to something now condescended to—mostly. Retro is currently cool in culture – vinyl records (even reel-to-reel); 35mm cameras and Polaroids; rock band t-shirts; high-waisted pants; cocktails and shaker kits; even IG filtres – but letter-writing hasn’t made the cut. There’s not much to package and sell to the practitioners of longhand. Maybe that’s why. Lives are recorded in letters. And the life around those lives laces the written lines, forming cultural records that capture and reflect for us the more intimate portions of collective life as they play out in private spaces. Why else would letters like the one above join collections in public archives, libraries, and museums? Letters contribute to our public history. If you type “letters” into Harvard library’s special collections search engine, and then “image”, you get 9,655 hits. If you do the same for the New York Public Library you get 18,038. What will happen 20 years from now, and 50, and beyond that? Will we publish emails? Not likely. Most of us delete our emails, and few of us turn to the mode with the tenderness, time, and tenacity it takes to correspond by letter. And we’d have to pass along our passwords to someone so that our emails could eventually be retrieved. Who do you share your passwords with? In any case, when’s the last time you lingered over an email—made a pot of tea, and settled into a comfy chair to read, and reread an email? Some don’t even use email anymore, or never really have, it too relegated to a generational joke. You know what I mean. I recently described to a millennial the functional hiccup I encountered on a website, and she suggested that it was probably because I’m “old” (she used air quotes), rather than considering for a moment that the platform and its navigation might be poorly designed and/or have had a glitch. It took everything in me to not roll my eyes and tell her that I’ve been using computers for longer than she’s been alive; that, apparently, though the web may be wide, her use of it as a conduit to the world seems to be pretty narrow, and narrowing. Ask Nick Cave about the power of a letter. No, wait, don’t—instead, listen to his 2001 ballad, Love Letter, an incarnation of the plaintive ache his composition is meant to remedy: Love Letter, love letter / Go get her, go get her / Love Letter, love letter / Go tell her, go tell her. What more is there to know about the potency of a letter? For the curious, the kindred, and the quixotic, letters also come bound and published as collections. I’ve read the collected correspondence between Al Purdy and Margaret Laurence, and between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz; next on my list is the published collection between Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark as well as the letters of Earnest Hemingway. I’m a letter-writer, which you’ve probably already figured out. I have a long history with letter-writing as well. My practice has always been the long letter, long in time to write which yields a letter long in pages. I’ll write over the course of a month or so. By the time I wrap it up, my sendee has accompanied me along multiple storylines in my life, the letter taking on narrative momentum a bit like a script might, but without the formal constraints of the three-act structure, resembling something more akin to Richard Linklater’s 2014 film, Boyhood, another manifestation of the filmmaker’s question: how do we cope with time passing? (Some letters help track what might offer answers to that question, or at least shed some light.) A storyline of mine, in a letter, might come to its conclusion within the span of the letter, or in the next one. Andrei Tarkovsky, another filmmaker whose work has expanded filmic language, wrote about his work and his aims as an artist in Sculpting in Time, describing film’s particular capacity to express the course of time within the frame. Letters do that too. I’m also into stamps, though I’m not a stamp collector. I always look forward to renewing my stash of stamps, making my selection based on the artistry and the message, little pieces of art I then send across the world. Right now I have round ones with chrysanthemums for international postage (there’s not a wide selection for international), a set of Voices of the Harlem Renaissance for domestic, and a set of coral reefs for postcards. It’s amazing how much there is to choose from—something to suit a range of tastes and interests. Do you remember Fargo? (The Coen brothers' film, not the series.) In it, running on a very minor plotline, Police Chief Marge Gunderson’s husband, Norm, is working on a painting for his submission to the federal duck stamp contest. It’s a thing. (Norm’s mallard earns him second place on the 3-cent stamp, a disappointment to be sure. No one uses the 3-cent stamp, he tells Marge. Of course they do, she replies, ever the pragmatic optimist and loving wife, whenever they raise the postage, people need the little stamps.) The duck stamp contest was started by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 as part of a conservation effort to protect wetlands and wildlife habitat, and it continues today. Conservationists buy duck stamps, knowing that 98% of the cost goes directly to protection work. Stamp collectors buy them to help increase their value, thereby increasing the returns to the intended conservation work. My first letters were written to my parents. To my father who lived far away from me as I grew up, and then to my mom, once I moved away from home. I love my father’s handwriting. It carries the same verve as the poems he wrote. I love my mother’s handwriting too. Once we began corresponding regularly I noticed that the W of my signature was very much like hers—a graceful line elongating the arc of the final curve. Over time I noticed how the way I wrote all of my last name had almost completely taken on the shape of hers—the looping lines drawing out the direct link of my lineage. To this day, I think of her each time I sign something by hand. And whenever I open the box where I keep the collection of our letters and cards to each other, our bond is illustrated in the assemblage of envelopes addressed to and from the same name, in the same script. After each of my parents died, I travelled to their cities to handle arrangements. This included going through their belongings, a strange and singular experience that mixes the past with the present, leading us to sometimes stumble onto secrets that might make sense of partial memories, and of family lore, helping to solidify one’s place and history, or at least to help illuminate it. My parents separated when I was an infant, yet I found letters between them dating from their separation to the time of their deaths. They wrote to each other as my parents, discussing me as I was growing through the stages of my life; and they wrote to each other as friends, across so much time and distance, and the troubles they each had. I found letters other people had written to them. And I found letters I’d written them. They’d each kept the letters.  Piecing everything together, I pieced together parts of my life I’d forgotten, with others I’d never known—some telling about me, some telling about the times. In it all, I learned more about myself, about them, and about their worlds. My mom wrote about the founding of Greenpeace, which was around the corner from us on W. 4th in Vancouver, and was where she volunteered. My father wrote about Mickey Munday, Miami’s Cocaine Cowboy pilot who lived down the street. And in a letter from my father to his, written when he 16 and in his first months of pilot training, I see in my father's maturing script hints of a  sterner man in my grandfather than any family story has ever told. It was the early 40s at the Randolph airfield in Texas and my father's attempt to fly for the air force an act of love on the part of a son for his father, an esteemed WWI pilot. The letter is written before my father failed pilot training. When I returned to Montreal from Miami where I’d gone to attend my father’s memorial, a postcard from him arrived in the mail. Postcards are often slower to make their way through the postal system, so it’s hard to know how close to his death he was when he wrote that card and mailed it to me. Included in the things I brought back with me from Miami was his suicide note, it in the same handwriting that swept across the postcard. I still have both.  Right now, I owe E. a letter. We’ve maintained our friendship through letters for longer than we’ve been friends in the same city. Occasionally we intersperse our correspondence with phone calls, and the rare text message, but it’s mostly our letters that hold us close. We send all kinds of things to each other in our letters. My last letter included several How-To Haiku zines I made so that E. and her Glaswegian pals could have a haiku-writing party together. Her most recent letter to me included a page torn from a small Muscat de Rivesaltes notepad, which I use as a bookmark (yes, I read physical books too ) and which I know she sent because she knows I love Muscat—it’s her promise to me that when we’re together next, we’ll go to her house in France where we’ll drink Muscat in the garden. Her letter also contained a little drawing illustrating something she was trying to describe to me about the nature of time. The illustration depicts E.’s woven Kabyle tray on the table beside her, it illustrating her point about time. There’s also the envelope, with its acknowledgement of Captain Sir Thomas Moore, the centenarian who started walking laps in his garden on April 6 to raise money for the UK’s National Health Service efforts to confront COVID (by the end of the day on April 30 – his birthday – his efforts yielded £32.79 million). And, finally, the Par Avion sticker there to remind us that this thing is not travelling to me by boat. Since the COVID lockdown, I also received a thank-you card from Our Community Bikes, one of my favorite not-for-profits in Vancouver. Working under the pressures this lockdown has caused so many, they held a fundraising campaign to which I contributed. They sent me this handwritten  thank-you card, mailed inside a hand-addressed envelope. No Avery type-printed address stickers for Our Community Bikes, and so none for me. For a while I was pen-pals with a woman in a Los Angeles maximum security prison. She was the mother of three, and was in under the 1994 three-strikes-you’re-out law. Her infractions were minor drug-related charges and traffic stops gone wrong. She was doing life.  For a few years in my early 20s I had a PO box at the main post office in downtown Vancouver, even though I had home addresses everywhere I lived at the time. (I once gave my PO Box address to a guy who asked for my phone number, telling him, cryptically, it was the best way to reach me, no matter what.) I loved picking up mail late at night, entering the quiet alcove of the post office, eyeing the others doing the same. Did they too have street addresses like me? I fell in love once through letters. We met at a conference in Banff, and then discovered that we lived 2,300 miles apart. And so when we each returned to where we lived, he to his small house on the Anzac reserve in northern Alberta and me to my brownstone walkup on the Montreal plateau, our courtship began by letter. He wrote in pencil, he explained in his first letter, because it’s more forgiving. And with that I was hooked. I once wrote a letter to my sister in New Zealand, and was so keen to be close to her that I photographed the pages and emailed them to her. And once, I wrote a letter to E. in Scotland, and photographed the pages to keep for myself, printing them out and pasting them into my writing journal to mine for ideas later. Years ago, in the wake of my parents’ deaths, I wrote often to L., my closest friend far away, who later told me and tells me still: I have all your letters. When you’re ready, they’re yours. I haven’t asked for them yet. Today, I’m a museum educator and I work a lot with senior high school students. No matter the project, I ask them to explore their ideas with a pen and paper because the brain behaves differently that way. When writing longhand, neural activity is triggered in particular ways—all good for cognition and creating. The field of research known as “haptics,” which includes the interactions of touch, hand movements, and brain function, tells us that cursive writing helps train the brain to integrate visual and tactile information, and fine motor dexterity. So, it’s spatial, cognitive, and kinetic. Other research highlights the hand's unique relationship with the brain when it comes to composing thoughts and ideas: a material activity, and slower than typing, handwriting forces us to rephrase ideas and concepts in our own words. So when I ask students to write by hand, they’re making sense of their learning, and their world, in their own voice. Additionally, the process of production that handwriting involves, each letter formed component stroke by component stroke, recruits neural pathways in the brain that go near and through parts that manage emotion. All this making learning both stickier and more holistic. These benefits are aren’t just for young brains. Neuroplasticity belongs to us all. We each have the capacity to continually change our brain’s architecture and operating system (neurons that fire together wire together). And it’s not just writing longhand that enhances positive neural rewiring—reading longhand does too. When we read handwriting, we activate the same neurological instructions required to write those same letters and words, something keyboard-written type doesn’t demand of us. So, basically, to read handwriting is to be empathetic. There’s also a heap of research on attention: how much, how long, and how deep our attention is when we read online versus reading something in our hands. It turns out that deep reading – the process of thoughtful and deliberate reading through which we actively work to critically contemplate, understand, and ultimately enjoy a text – is compromised when we read on a screen. When we skim and scan a lot, and surf from hyperlink to hyperlink, our brains get good at skimming and scanning and surfing – to the brain, all shallow activities – and less good at neurological deep diving, the kind of brain capacity required for concentration, contemplation, and reflection. So, as we reroute our neural pathways online, we are remaking ourselves in the image of the internet—the medium is indeed the message. I remember a day in 1996 when I gazed for a long time at one of the first advertisements for a wireless phone. The billboard presented the image of a pristine conifer forest, sunrays filtering through the grove of trees, with the words finally free plastered across the tree tops and reaching into the sky--two little words redefining the concept of being untethered (just two of the many that have grown into the barrage of lexiconic gaslighting we have today). Alternate facts, indeed. These days, more than 20 years since that ad came out, in an attempt to simultaneously unplug and reconnect, people now pay to attend forest bathing workshops in groups that are led by somebody who asks that phones be turned off.

There are tangible costs and consequences to those today who choose to opt out or who limit their participation in the online world. From being mocked and called a Luddite (go read about the Luddites, they’re pretty interesting), because, apparently, it’s unchill to step away from monolithic click-bait corporations instead of capitulating to the transactional interests of their opaque business models (like FB [uber uncool] and its millennial-pacification do-over, IG); to more culturally ubiquitous and coercive expectations, silent and tacit, that you must migrate your life online to work in today’s economy (think LinkedIn), even if your work takes place off-line. It’s not called the attention economy for nothing. I don’t want to go fast and break things. I don’t want to lean in. I don't want to curate my life, and pin it. I don't want to follow influencers. I don’t want to read Toni Morrison on a backlit screen. I don’t want to use performative platforms to maintain my powerful friendships, especially when a long stretch of Earth keeps from us being together in person. I don’t want market-driven algorithms driving my information, my attention, and me. I’m not a consumer of content, I’m a sentient being, animated by caring, curiosity, and concerns of all kinds. I’m not a content creator (a stunning piece of language that so baldly reveals the vacuity of the enterprise), cranking out filler for the spaces between the ads. I’m an artist. I’m an agent. A citizen. I choose analogue channels. I choose digital channels. I choose. I wonder about those who don’t write by hand anymore, and those who don’t correspond by letter. In a world absent of handwriting, and where no one writes letters anymore, there’s an empty mailbox, an empty archive, and what more? It would seem there’s a lot to lose when we put down the pen. We lose connection, we lose our unique dimensionality, it looks like we're going to lose pieces of our histories both personal and public, and, apparently, we’re losing our minds. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees. Maybe experiencing forests by paying someone who first tells you to turn off your phone while you’re there is a good sign that there’s a system glitch, a big one. I’ll check the mail later. I always know when it arrives. The postman on this route talks on the phone all the time. He has on a headset but he’s loud. I can even hear him when he’s driving up and down the street, his cheerful holler blasting from the open truck doors. But for the moment, I’m going to go inside and type this up. (You knew I was writing this by hand, didn’t you?) I wish there was a way for your read it as it is. Not this time. PS: I was prompted to write this essay for work. While the museum remains closed, we’re all pitching in to produce virtual experiences, including writing pieces for the blog. With the threat to the US Postal Service on my mind, I offered to write something about letters. Writing on commission is unusual for me. I loved working with a gifted editor, and was interested to see how and where my personal voice had to conform to an identity other than my own. Here's the version of this piece that went up on the museum’s blog. It’s pretty different. (And, no surprise, the blog version is a lot shorter—I was told that people just don’t want to read anything too long. So, the dictates of the medium do indeed dictate the message.)

1 Comment

|

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed