|

Fourteen months into the pandemic, I was waylaid by a lassitude I couldn’t kick. I had it bad — I couldn't even stay inside a novel because my capacity for deep and sustained focus was gone. Then I read Adam Grant’s 4/19/21 NYT opinion piece, There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing. Yup. That’s it. That’s me, I thought.

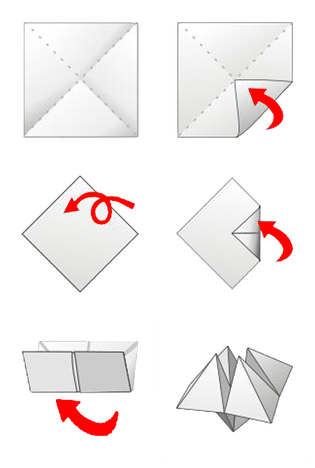

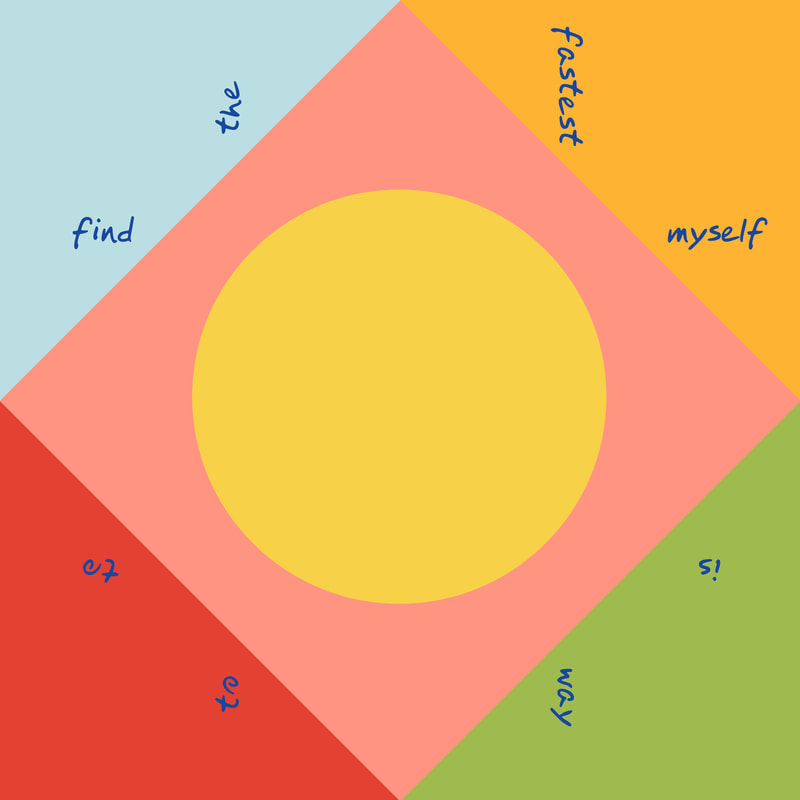

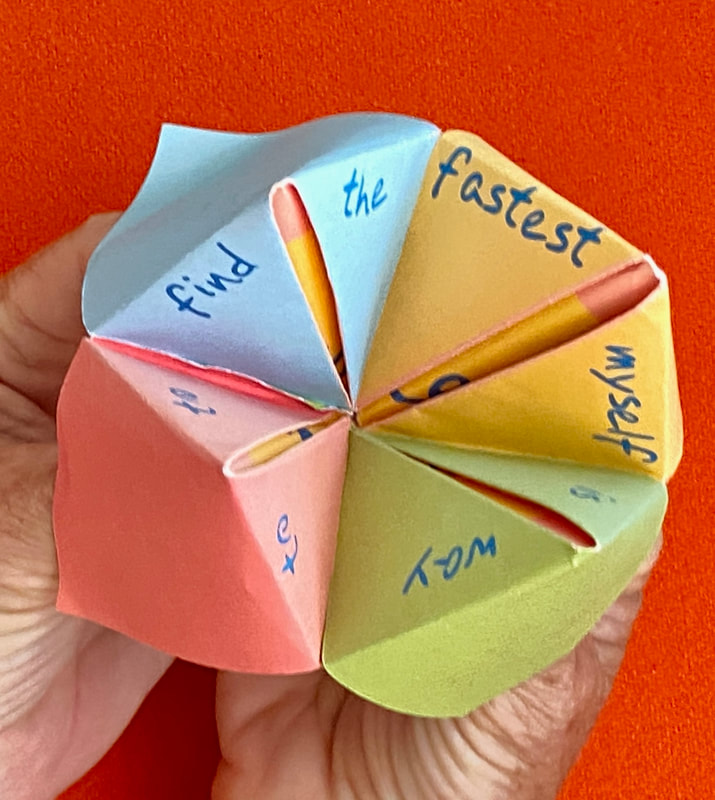

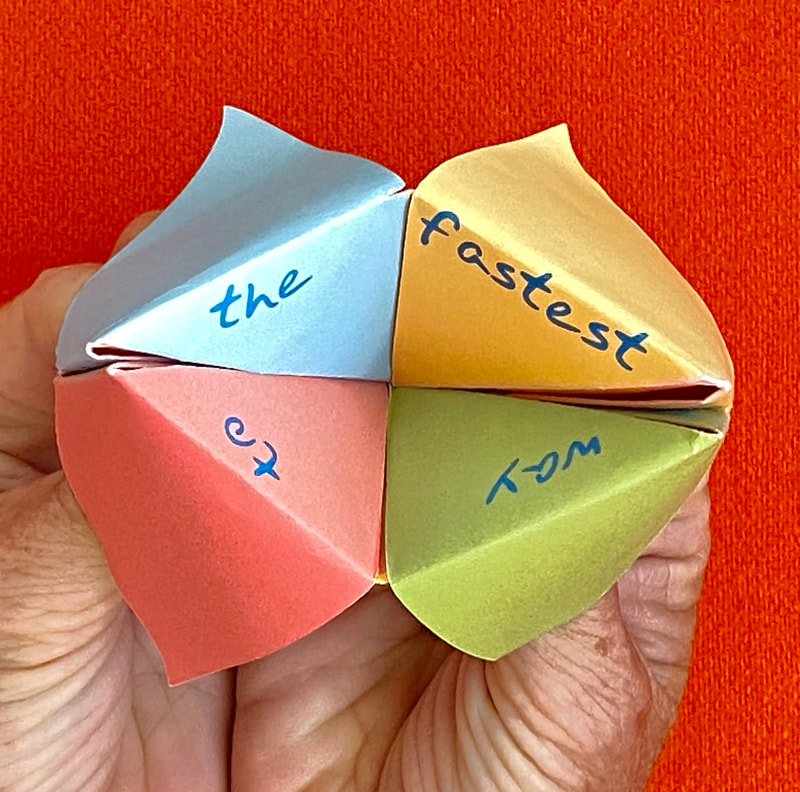

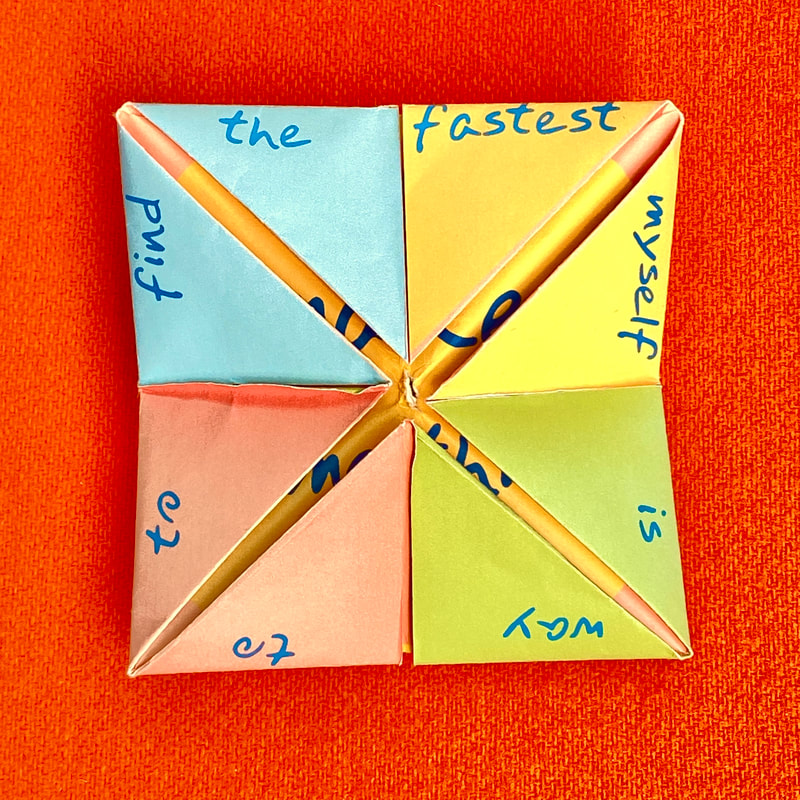

To get myself there, I went over to my work bench and fiddled with some paper, sticks, pens, glue, thread, and whatever else was laying around that day. Eventually, this is what I made. It has a lot of different names — fortune teller; chatterbox; coin-coin (in French) — whatever it’s called, here's the one I made as my gateway to getting out of languishing. It says: the fast way to find myself is to Then I answered my own question: the fast way to find myself is to For me, making something is a sure way out of a slump; to get myself out of languishing. It might be different for you. Try it out. Give it a whirl! Make one for yourself. And then answer the question: the fast way to find myself is to Here's how it works.  Take a square piece of paper and follow these folding instructions. Once folded, word by word, write on each of the 8 triangular tabs pointing down: 1 • the 2 • fastest 3 • way 4 • to 5 • find 6 • myself 7 • is 8 • to * you can use the photo below as a guide because the 8 words don't run in sequence Next, give some thought to how you would complete the statement. What does lead you back to yourself?

When you have your answer, open up the flaps and write it down on the inside. You can make as many as you like. You might find that your answer changes. Mine do. Yet each one is true. I save mine. I set them atop tables and windowsills around my apartment as friendly reminders. I’ve really taken this to heart. I keep this one – make something – on prominent view as a mindfulness touchpoint, to remind myself to notice how I’m feeling, and then, super helpfully, what I can do next. And you know what? It works every time.

0 Comments

We girls all wore brown pleated pinafores, the kind with a bib and a belt that cinched at the waist with a metal buckle. Beneath it was a crisp golden cotton button-up shirt. It must have been cheap cotton, something poorly woven or starched to hold its structure, because it slightly scratched at my skin below. In the winter we worn brown leotards, and the rest of the year brown knee-high socks. My mom dyed a batch of my underwear to match the colour of my pinafore, completing the uniform and my adherence to it. I wore them over my regular underwear, turning the outer pair into something more akin to tiny pants under my skirt, part of the uniform; so when I hung upside down on the monkey bars with my belt undone and my pinafore falling inside-out over my head toward the ground, I didn’t think I was doing anything improper. I wonder if my mom was required to make that undergarment for me, or if she took the initiative on her own—a small gesture toward ensuring I fit in. Probably. All for a little private school a few blocks away from where I lived at that time. It was actually a three-storey house, a mansion refitted as a school. This was not a school for the elite. There were no preening parents conscientious about our grooming. No chauffeurs gliding up to the curb; no nannies clasping the little hands of their charges. We were the opposite. We were the children of single parents: those separated and possibly divorced, some probably widowed, and some maybe never having been married at all. It was a time when no one spoke about these things. They were connections we would figure out later, looking back. When the school day was over, we stayed, supervised as we played in the large yard until we were each picked up by a parent to go home. It was the only school with such a service then. It was a good school. Small classes. Boys and girls comingling on the playground, something unheard of at the time. We had French lessons and made our own butter, slowing churning cream by turning our mason jars each afternoon, end over end, our little hands clutching carefully so the glass wouldn’t slip and break, destroying our alchemy before the magic took hold. After each churning session we set our jars on the windowsills in the autumn chill outside, our names in childish script identifying whose was whose. Through the pane, there was mine, Elizabeth looping across the label, the contents well on its way to becoming solid. I attended grades one and two at this school, and did very well. I loved school and school loved me back—my marks were good then, and I felt proud of my work. Then came the antonym test: words stacked in one column on the left side of a sheet of paper had to be matched with their antonyms on the right side. It was my job to do the matching. Across from rough, I wrote calm. When my test was returned to me, calm was crossed out in red ink and smooth was inserted in its place. I lost points. All six years of me was incensed. From summers spent with my cousins at their family cottage beside a lake, where all the older kids waterskied and everyone would squint at the water each morning to see if the surface was flat and good for the first spin of the day, I knew for a fact that the opposite of rough was calm. When the water is calm, we waterski; when it’s rough, we don’t. Still too little to ski myself, I was the spotter in the boat. I watched the waterskiers to keep them safe, eyeing the waves for all signs of threat. I knew water and I knew its surface. All us kids did. _________________________________ Ellen Langer tells a good story, one I wish I’d heard when I was six and I knew that the opposite of rough is calm. Langer is a Harvard social psychologist. Much of her research looks at how our experiences are formed, perceived, received, and understood by the words we attach to them. Langer talks about questioning assumptions, examining common axioms that come to dominate our perceptions and precepts and dictate how we frame knowledge. Make no assumptions, Langer says, or at least be aware of the assumptions with which you operate. Things aren’t always what they seem, nor are they always what we think they are. Langer gives examples. Good ones. Simple. Clear. Effective. Empowering. Examples like this: if you take one piece of gum, put it in your mouth, and start chewing, and then you take one more piece of gum and add it to the one you’re already chewing, you still have one piece of gum in your mouth. If you have one pile of laundry on the floor and you then add one more pile of laundry to it, you still have one pile of laundry. 1 + 1 = 1. The opposite of rough is calm. _________________________________ At six years old, I was the victim of epistemic injustice, I know that now. Epistemic injustice is the act of wronging someone in their capacity as a knower. The term was coined by Miranda Fricker, Presidential Professor of Philosophy at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Epistemic injustice straddles the fields of philosophy (ethics in particular) and epistemology, looking at the construct that is knowledge. In broad terms, it’s concerned with how social power operates and how it’s attributed to individuals and groups, particularly through the many lenses of the official story: empire and post-colonialism; gender; race; economics—basically looking at anything humans get up to—ultimately, examining who gets to define reality. When applied to the operations of education, epistemic injustice looks at the meta: academe and the cannon; and at the macro, in the classroom, concerned with the power dynamics at play between teacher and learner. Epistemic injustice reminds us to consider who gets to decide what’s the opposite of rough. _________________________________ I work with high school kids now. I’m not a teacher. I lead a project that takes me into several high schools each year, involving hundreds of students. I tell the kids in each class about my six year old self knowing that calm is the opposite of rough. I share Langer’s examples of gum and laundry. Because I know about epistemic injustice, I make a point of doing so. I want them to know that 1 + 1 can = 1 The last time I did, I noticed a quiet kid at the back of the room. Long and lanky, his body stretched well past what his chair could accommodate. As I was talking, I saw a curl appearing on his lips, his eyes brightening as his eyebrows gradually lifting higher on his forehead; and as he slowly began to speak I saw illumination emanating from all over him. Wow, he said, you’re blowing my mind right now. Yes, I thought to myself, Blow your mind wide open. And please try to keep it that way. Oh, one last thing, I said as I was getting ready to leave, life can be rough, so try to take it calm and smooth. All the kids smiled. I've been waiting for the official announcement so that I can make my own - "official" might be an overstatement, but public it now is: I have a piece selected to wrap a bus shelter in Seattle!

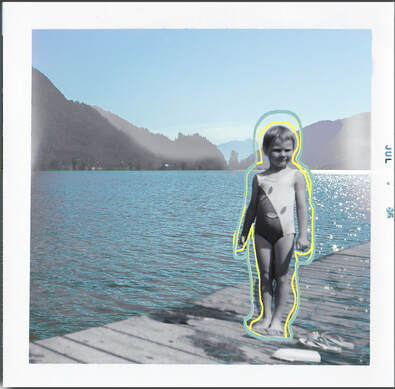

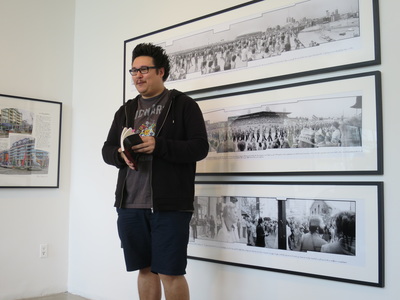

The City Panorama 2016 competition was hosted last winter by Photographic Center Northwest and King County, and my piece was selected as one of 110 out of 1500 competitors! The announcement was kind of quiet, but the list of finalists is at the bottom of the call itself. Here's the piece they selected. It's 8' x 2', and I call it Slocan Skipping Stones; it's of Loïc skipping stones on Slocan Lake when we camped there one summer. It's wrapping a bus shelter at 3rd & Union, right in downtown Seattle. So, go take a bus!  Vancouver Saturday January 23, 2016 Burrard Arts Foundation / PuSh Festival He doesn’t know it yet, but Harold Budd composed the music for my 1987 Super-8 film, “Call”, an experimental piece, running time all of 5 minutes or so. I’m going to tell him today, almost 30 years later. Budd is in conversation with Alex Varty at *BAF this afternoon, as part of the PuSh Festival. I arrive early, so pick what seems to me like the best seat in the house, a bearing beam at my back that I can lean into, and an unfettered view of the two empty chairs positioned under the soft gallery lighting and amidst the even softer colours of Ed Spence’s paintings currently on exhibit. I’m excited, to understate things. They arrive and take their seats. Harold Budd is a dapper man, diminutive in size, august in dress, elegant in manner. Alex Varty is nervous, or seems so; maybe that’s just his way. Budd is relaxed and offers simple responses to Varty’s questions—he’s not being rude, he’s just modest, with a well-hewn sense of himself. When asked about a particular collaboration, if it was the other’s technique that Budd enjoyed, he said of his collaborator: it was his attitude; that he came at his work, like me, with the view to be alert to what you adapt as real into your own material being. This seems key – Budd’s leitmotif, for living as much as for working; it seems to be about finding what produces harmony in space, both in the one he inhabits within himself and in the one that surrounds him. He seeks out beauty. Long ago, he said, when his son was born, he moved his piano out of the living room, and filled in the space with a Navajo rug where they lay and played. He said he found the piano really ugly, and found the rug very beautiful. By way of further explanation, he said it’s part of his avoidance of confrontation—he’s had too much of it in his life, and so seeks out beauty. I’m a man who loves flowers, he said of himself, in sum. To me, he’s a fluid man. He doesn’t attach to much, but he’s not aloof either, just loose: he doesn’t get attached to things or ideas, nor does he probe much for meaning. He’s ready to be content with what is, though making sure that circumstances are opportune for contentment. Budd started out long ago, he told us, feeling his way towards his own interests through intuition and inspiration. In 1956, he saw a Rothko painting in a book, and in it he saw a way of living, and a way of making a living; he saw where he wanted to be, and then he got himself there. He’s ever since followed his intuition, and says he works on hunches. Today, if a hunch doesn’t pan out, he diverts route. With “too many loose ends in my brain”, he says, he doesn’t try to analyze what he’s doing, he just tries things out; if it’s not good, he moves on to the next thing.  Varty’s last question to Budd surprised me: he asked about the pink-tinted glasses Budd wears, who then explained: I don’t see well anymore, and I live in the desert where it’s really sunny. The rose tint reduces a large amount of glare, while protecting my eyes from bright sunlight, and they also provide sharper contrasts between objects so that I can see better. I know from glass artists that pink glass is the most expensive because pure gold is used to produce the pink hues; I also know from an anthropology major that the pink glass that was used in old cathedral stained glass windows was considered the highest spiritually, likely because of the cost to produce it, and so, used sparingly, it was tied to the most significant elements, often used to represent Mary. It occurs to me that Harold Budd sees the world, as the saying goes, through rose-coloured glasses. I think it perfectly applies to him, in every way—call it a hunch. PS: After the talk, I introduced myself to Harold and told him the story about my film. He was gracious to me, and amused by the story, and he kindly autographed the S-8 cover. He held my hand the whole time we talked. He's 79. I'm excited. No, I'm ecstatic. I'm in Montreal this summer, where another of my most favourite public art pieces is out again. 21 Balançoires (<-totally click on that), by Montreal-based design house Daily tous les jours, is an interactive musical installation that plays best when people join to play on it together. It's a sensorial wonder, evoking memories, connections, and tenderness where words don't reach - oh, it also makes music. I missed it last time I was in la belle ville, but it's annual spring appearance is being carried over into the summer this year I hear (<- click to listen to the April 29 show at 8:29 minute mark). This is place-making at its most breathtaking. I can't wait. I'm a life-long swinger*. I swing when I'm happy. I swing when I'm sad. In the summer, I swing almost every day, and sometimes late on a warm night too. I never tire of it, and am constantly surprised at how much joy I experience gliding back and forth through the air, flying and diving at the same time. Can't wait to share this. À bientôt les 21 balançoires! Here's a little snippet ... * I mourn the loss of some of the older words - swinging, thongs, kangaroo jacket, for example - now needing to explain myself when I use them. I'm very attached to these words, or perhaps it's to the era when they were actively used, so innocently it now seems.

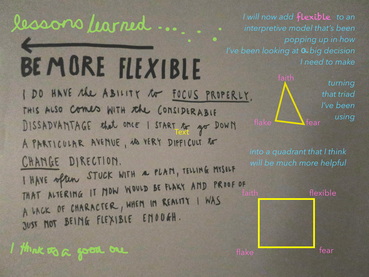

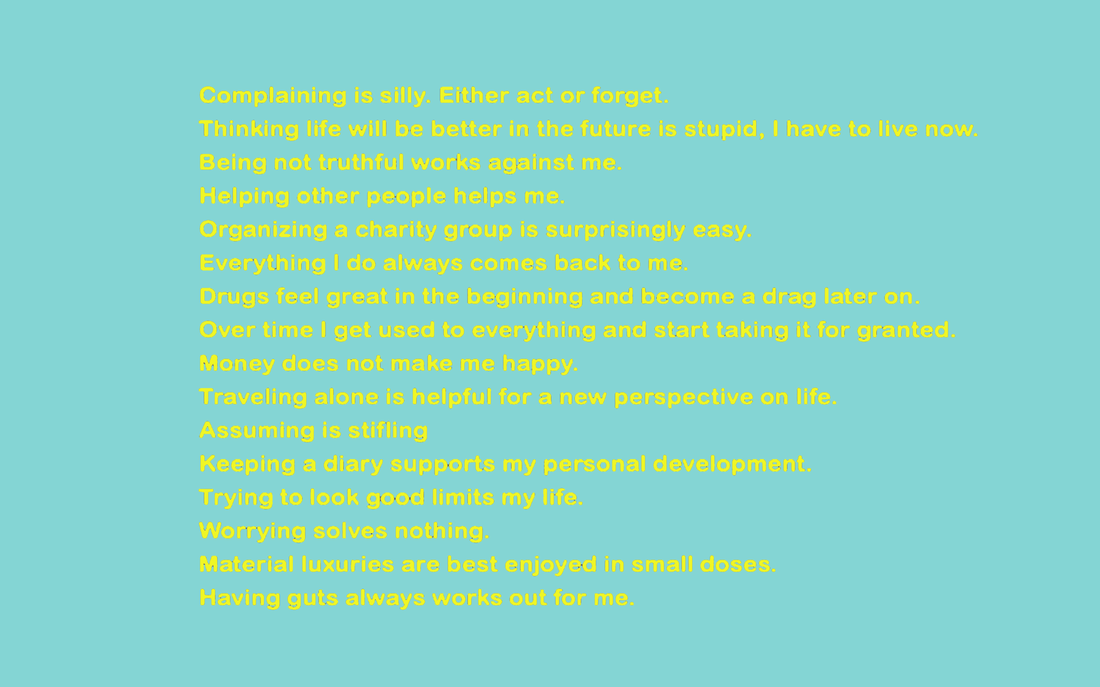

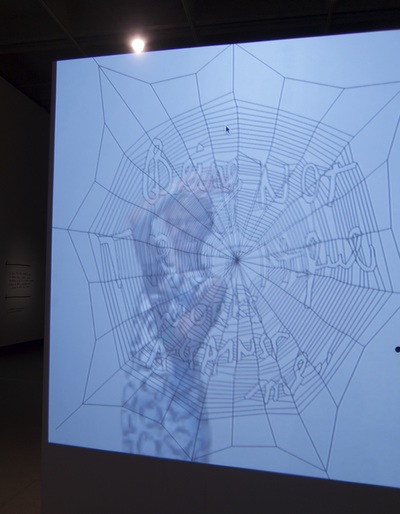

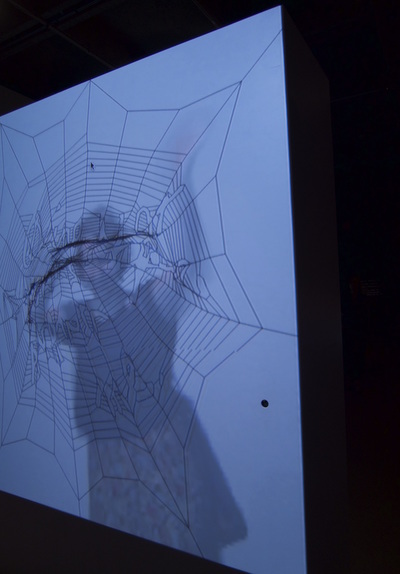

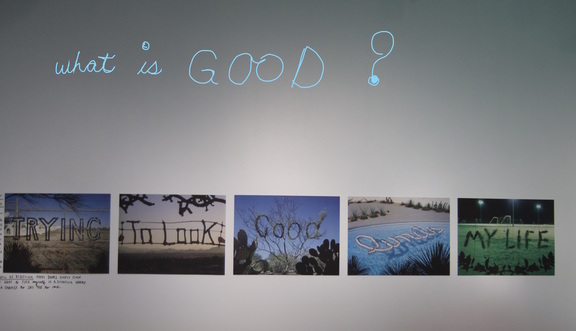

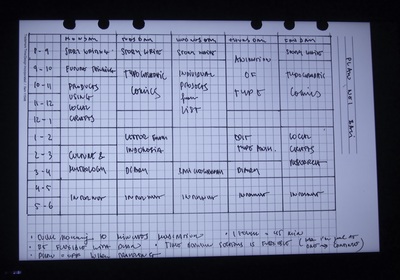

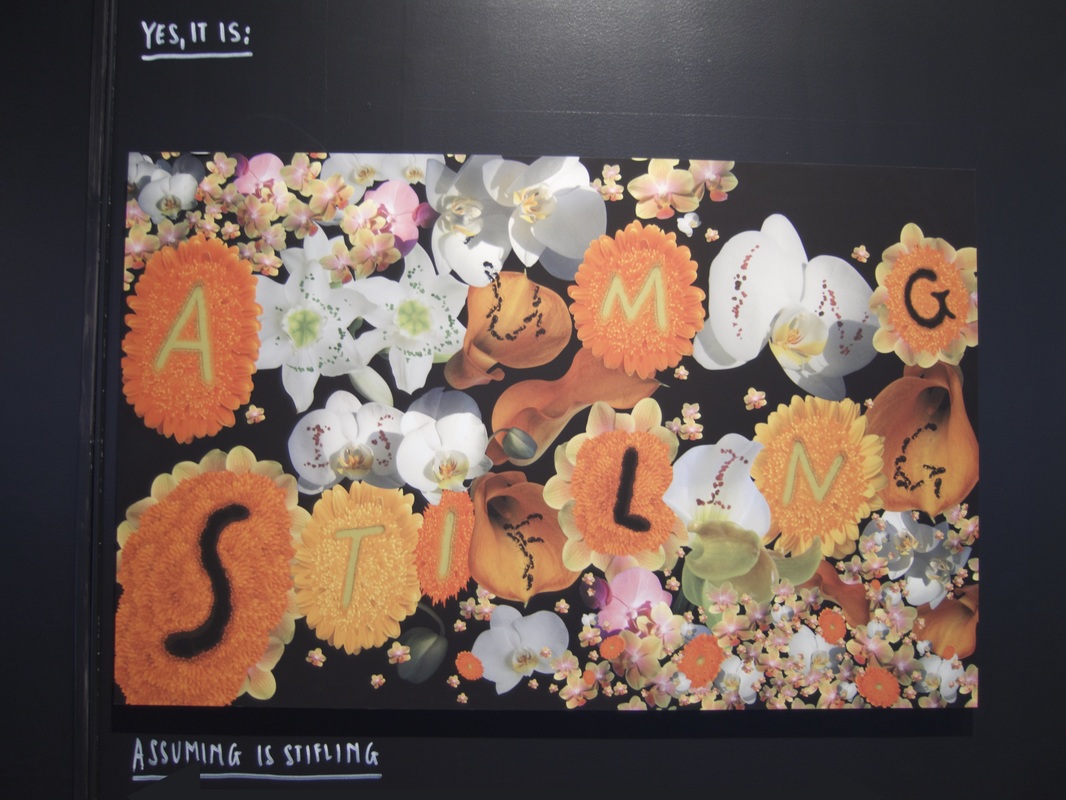

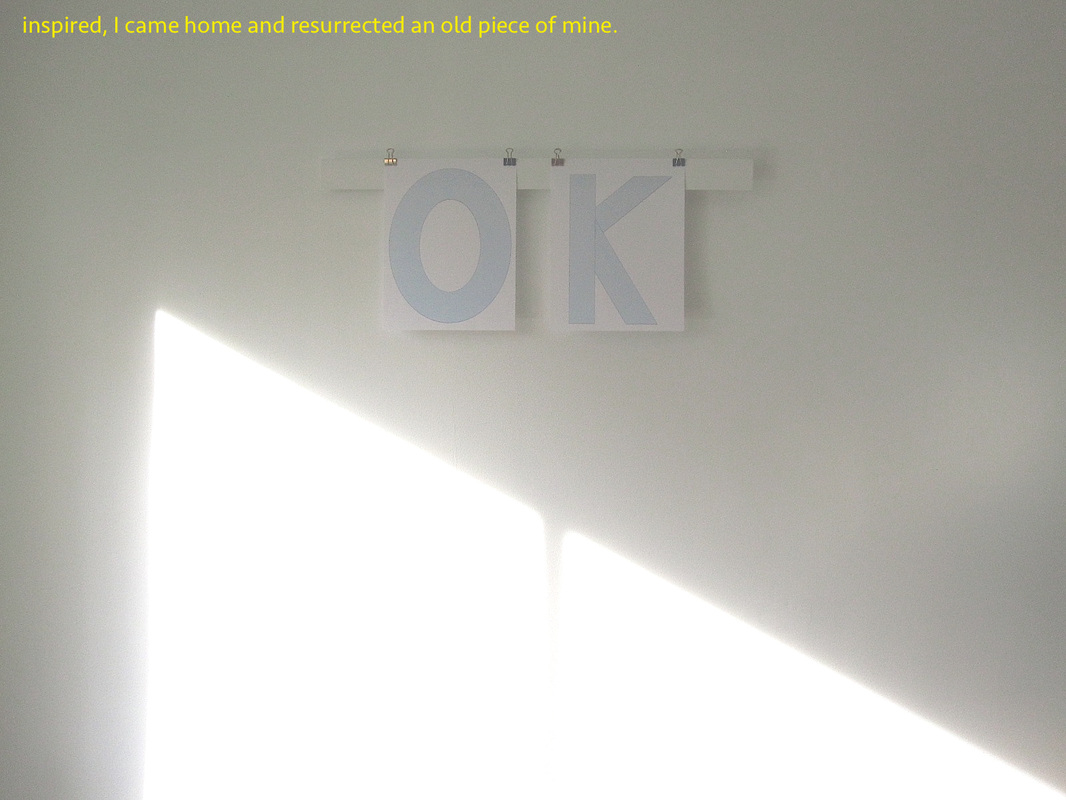

Maybe it's that loss of innocence, that gentler time, that I yearn for. When I ran around with thongs on my feet, sometimes stubbing my toe because the flimsy rubber sole folded under itself; the kangaroo jacket, that handy muff (another word) pocket in front where anything shoved in there could be readily accessed by either side, and a hood for warmth at night by the fire; and my beloved swinging, an activity whose word for it conveys the unfettered freedom and fun of this spectacular experience, now plunged into the murky underworld of fringier experiences that have laid claim to that once perfect word. So, I finally got to myself to The Happy Show! Terry and I went yesterday. Like freeform cheeseballs, we listened to Pharrell's Happy on my itouch as we danced our way into the exhibit. Why not?! I've been very excited about the show, having streamed all I can find on-line in the way of interviews and talks with Sagmeister. For over a decade, he's been researching and experimenting with what makes happiness, and his own in particular, and the show synthesizes some of what he's discovered. Here's a slide from a TED talk he gave - it really grabbed me, so I screen-grabbed it, and then changed the colours. It's an outline of what he's discovered "works" for him, a concept I'm now fleshing out for myself (I'll share my list when it's done). Here's his list. Some of the maxim's show up in the exhibit. And here's a bit of The Happy Show, as experienced by me and Terry yesterday. A very awesome interactive piece, expressing the maxim: being not truthful works against me. This is me and Terry discovering it - then we started dancing in front of it, and running back and forth. Yes, we were the loud ones at the show. Our answers to the question: what is your symbol of happiness. Trying to look good limits my life. Good maxim. When I read this, first at home and then again at the show, each time I thought it referred to the concern with how we look in terms of our appearance: as in how we're dressed, our hair cut, and so on. Surface. (Maybe it's the clothing designer in me.) Terry read it as meaning a concern for how we appear to others in terms of our behaviour, our choices, our way of living, our gestures, and so on. Substance. Either way, the concern for looking good is limiting, restricting our spontaneous expressions of self, arguably (maybe) censoring those most authentic manifestations of who we are. Grooming vs/ hygiene, and finding the limiting line. Authenticity vs/ obnoxiousness, and the location of that line. Perhaps, the boundaries to watch out for are the ones that maintain balance. I've long believed in the social function of beauty, what some call looking good, my take on it extending from surface to substance. It's good to be reminded of this.  I'm struggling with very big decisions right now, and finding myself ricocheting around a triangle whose points of contact are faith, fear and flakiness. I love Sagmeister's take on flexibility and how it interacts with flakiness, so I'm working it into my mind model as I make this big decision. His piece is in black; the coloured stuff is mine. His work plan for a sabbatical. I took notes (well, a photo) to inspire my own scheduling of the impending vastness of time before me, the vastness I'm stepping up to. Another maxim: assuming is stifling. What I like about this is its activeness. Unlike that other one, assuming makes an ass of you and me, Sagmeister's angle tells us something useful to consider in terms of our expectations our intentions and most interestingly (to me) our agency in the ways we live and engage with what's around us. My conclusion. This is a shot of an old installation I put up in my place a few years back. Leaving the Happy Show yesterday, I thought of it as my response to the experience I had there. dernier mot:

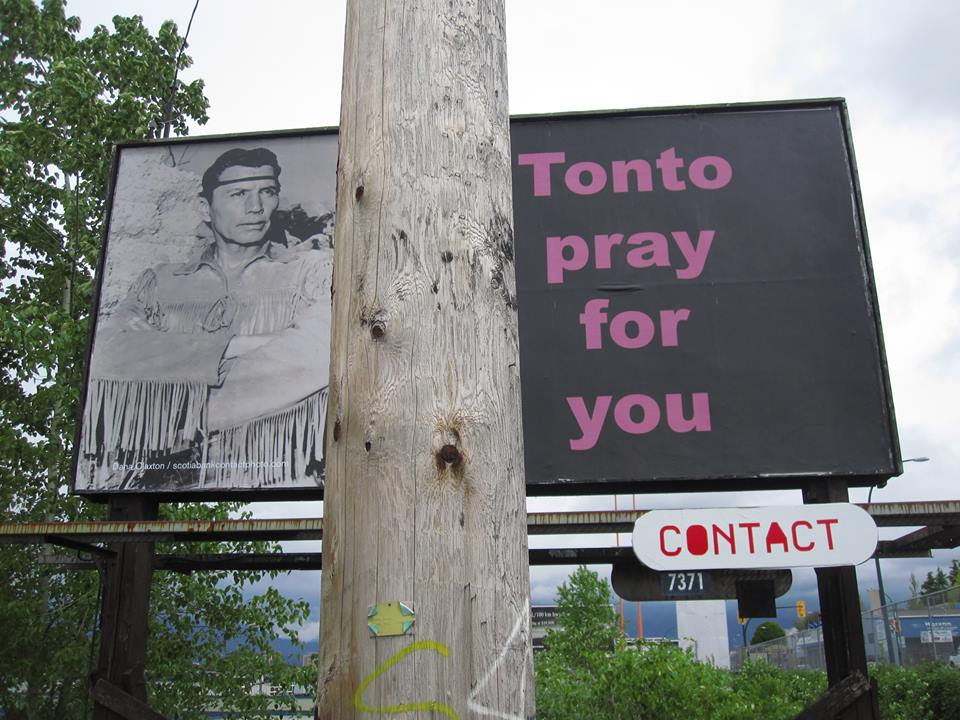

As Terry and I watched the 12 minute clip from Sagmeister's The Happy Film, I commented on a sense of melancholy I feel coming off the man and his work; Terry called it longing, which is a good word for it too. Sagmeister rates his own level of happiness quite high, and there's tangible euphoria in what he makes, yet ... Maybe Terry and I are off the mark, yet ... I now wonder about the possibility of being happy and wistful at the same time. I think it's possible. I think it's common. I think it's human. I think it's ok. I'm pretty excited. The Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival in on, and a nearby billboard again becomes my favourite, proving one can have such a thing. Last year, as now, I happened upon the site by accident, as I biked along a weird back route to get to Our Social Fabric (another highlight in town). There's nothing like being dazzled by surprise. An unexpected encounter of the non-commercial on a commercial surface; art for all. So, head on over to on E. 2nd, just slightly west of Clark Drive. from his BAU Series, by Takashi Suzuki, May 2015 Tonto Pray for You, by Dana Claxton, May 2014

There's a great new piece of public art in Vancouver, thanks to the brilliant Vancouver Biennale. I completely love this piece - Trans Am Totem. The location is provocative, as are its elements. The piece sparks a fast stream of ideas in me, leaping together in free association. Here's what that stream produced: I call it Trans Am Totem ToMe, and it's also running on the Vancouver Public Space Network blog. (A great Vancouver organization, by the way, that works to champion the importance of public space and to the overall liveability of the city - all on volunteer steam.)

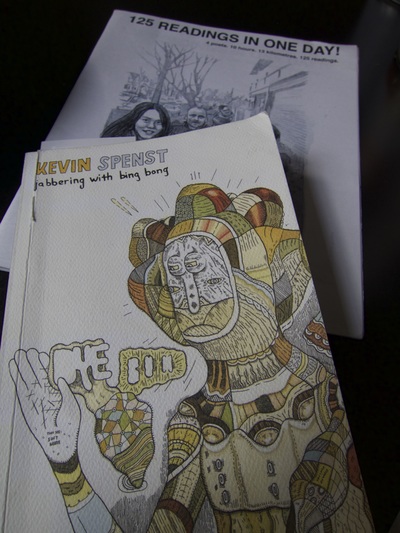

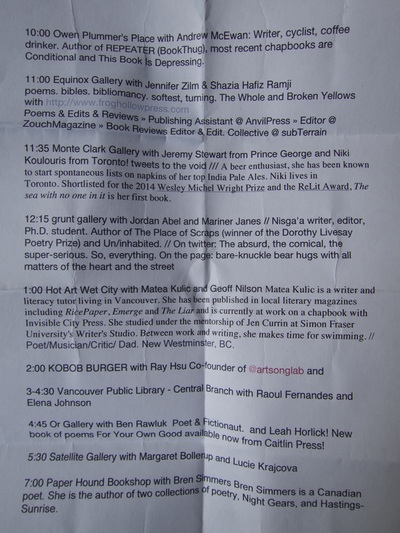

I was part of a super fun neighbourhood poetry crawl over the weekend, and I wrote about it for the Vancouver Public Space Network (my current volunteer gig).

The Vancouver Poetry Crawl 2015 was organized by Vancouver poet Kevin Spenst, and began at my neighbours Terry and Owen's place with a pot-luck breakfast; from there, the crawl ventured into neighbourhood art galleries, connecting ten venues where eighteen poets read their work. You can read the whole story about the crawl on the VPSN blog, and below you can find the visual recap of this out-of-the-box poetry extravaganza; if you click on the photos you'll see captions to offer a bit of info on what you're looking at.

a documentary directed by Marcelo Mesquita and Guilherme Valiengo about São Paulo’s street art and artists, particularly Os Gêmeos, Nunca and Nina a piece I've written for Pull Focus, a cool Vancouver organization that happens to be founded and run by a friend of mine.

Art is communication, art is connection, art is even war. In the case of São Paulo, Brazil’s sprawling grey city, and in the case of the documentary Grey City about some of São Paulo’s artists, the terrain for this art is the street, more precisely the walls in the street.

In the 1980s, São Paulo took the world stage as the epicenter for urban visual street art known as pixo — graffiti and tagging. Its antecedents, Pixação, “wall writings", originated in São Paulo in the 1940s and 50s when citizens painted political statements in tar on walls in response to political slogans painted by political parties. Pixo’s evolution through to today has maintained that spirit of dialogue and defiance—a kind of urban calligraphy where some of São Paulo’s most marginalized endeavour to tag as high as they can, in as many public places as possible, incontrovertibly asserting their existence as a form of challenge to the city’s privileged who consider pixo ugly, ignorant, and illegal, much in the way they view the pichadores (the pixo makers) themselves. The 80s re-emergence of pixo was an organic extension of other street art forms like hip hop and break-dancing. Such was the route for Os Gêmeos, the twin brother graffiti team featured in Grey City. With the same nimbleness of their breakdancing, identical brothers Otavio and Gustavo moved toward paint, starting first with pixo and then expanding their work into more pictoral murals. Today, their early pixo style can still be found within their murals, and the impetus to connect and converse with their city is at its heart.

Os Gemêos is out to communicate, to engage, and to contribute something positive for the public good—these are their guides. Producing their work during the day is critical to the process and to their pieces: how else will they know what’s going on, what they need to say, and to whom? How else will they connect directly with people and engage in real time? That’s how they see it. And what they encounter speaks back to them through the smiles and joy returned by passersby—this enthusiastic feedback loop affirming for them that they’ve honoured their vocation and their destiny.

Graffiti, however, also operates within the framework of the city’s regulatory, mercantile and political interests. So the war this artform engages in is often with the clean up crews contracted by City Hall to paint over the murals not deemed to be “artistic”—so, armed with grey paint, a subjective and anonymous army disappears the art, randomly and arbitrarily. However, in a metropolis of almost 20M people that sprawls across almost 8,000 square kilometres (the largest city of the Americas), the effectiveness of the clean up efforts doesn’t really keep pace with the artists, and so a kind of dialogue reverberates between leagues of creative resistance and the amorphous apparatus mobilized to squelch it. This is where the graffiti movement truly embodies its role as a public art. No one possesses it, directly challenging the fundamentals of capitalism, and no one really controls it either, though many try and wish they could. In the case of Os Gemêos, their rigorous code of conduct keeps their work “clean”, in the sense that their concern with public good means shunning any form of negative messaging, and their tireless commitment to producing such work, in proliferation, eventually attracted international attention, rendering their colourful contribution to the city’s walls more and more challenging to object to.

Os Gemêos’ progressive rise to worldwide acclaim has ironically jettisoned their work to the reaches of national sanction too: they were commissioned to tag the plane of Brazil’s national football team competing in the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Perhaps, though, this is a most apt illustration of remaining true to the artists’ animating values—speaking truth to power—in this case attaining lift off with jet engines; though, told not to paint the jet’s engines covers, they did it anyway, ever true to another animating force of the grafiteiro, tagging where authorities don’t want you to. Perhaps not quite biting the hand that feeds them, we could fairly say that Os Gemêos is willing to paint it.

Here in our own grey city, Vancouver is now home to the latest Os Gemêos piece, Giants, thanks to Vancouver Biennale and their partnership with Ocean Cement on Granville Island. Giants is an ongoing Os Gemêos project, adding Canada to the Giants growing international family of Greece, USA, Poland, Portugal, the Netherlands, Brazil and England. As Os Gemêos believes, “Every city needs art and art has to be in the middle of the people”, so Vancouver now has art, in the middle of the city, and this art happens to be a kind of people in its own right—Giants—an excellent symbol of art’s enduring heart, which is 3 dimensional, multiple, central, colourful, and gigantic. Here's the film trailer .....  One thing ends, another begins. I'm closing my business down, the one I've focussed on for the past 3 years. ad lib has been my clothing design company, a project full of interest to me. I've loved it. And now I'm leaving it. I start something new tomorrow, income-earning-wise that is. When my store closed a year ago today, I was already into the next thing in my personal practice - this right here: zoetrope.me I'll always make things. It's in my blood and my brain to do so. I'm born this way. My ultimate motivator is beauty - making beauty, making what I imagine beauty to be in a broad sense: as part of living well, in gesture and endeavour, expressed through all the ways in which we engage the world around us day by day—beauty writ large. I understand clothing on this grander scale, as more than how we cover ourselves: it's about how we carry ourselves, and how we conduct ourselves, culminating, most importantly, in how we concern ourselves with the world around us and how we care for it--it’s being conscious and conscientious. I will now transpose this concern for beauty into other concrete forms of work that I pursue. In this external one, this new income-earning thing I start tomorrow; and in all my creative work making things. Most importantly though, I'll continue to bring my concern for beauty into how I behave. Towards others. Towards myself. Towards the space I occupy, large and small. And so it goes. Next! |

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed