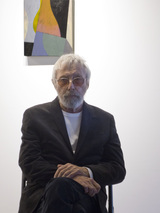

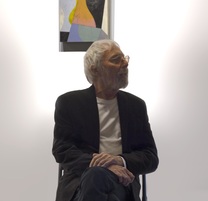

Vancouver Saturday January 23, 2016 Burrard Arts Foundation / PuSh Festival He doesn’t know it yet, but Harold Budd composed the music for my 1987 Super-8 film, “Call”, an experimental piece, running time all of 5 minutes or so. I’m going to tell him today, almost 30 years later. Budd is in conversation with Alex Varty at *BAF this afternoon, as part of the PuSh Festival. I arrive early, so pick what seems to me like the best seat in the house, a bearing beam at my back that I can lean into, and an unfettered view of the two empty chairs positioned under the soft gallery lighting and amidst the even softer colours of Ed Spence’s paintings currently on exhibit. I’m excited, to understate things. They arrive and take their seats. Harold Budd is a dapper man, diminutive in size, august in dress, elegant in manner. Alex Varty is nervous, or seems so; maybe that’s just his way. Budd is relaxed and offers simple responses to Varty’s questions—he’s not being rude, he’s just modest, with a well-hewn sense of himself. When asked about a particular collaboration, if it was the other’s technique that Budd enjoyed, he said of his collaborator: it was his attitude; that he came at his work, like me, with the view to be alert to what you adapt as real into your own material being. This seems key – Budd’s leitmotif, for living as much as for working; it seems to be about finding what produces harmony in space, both in the one he inhabits within himself and in the one that surrounds him. He seeks out beauty. Long ago, he said, when his son was born, he moved his piano out of the living room, and filled in the space with a Navajo rug where they lay and played. He said he found the piano really ugly, and found the rug very beautiful. By way of further explanation, he said it’s part of his avoidance of confrontation—he’s had too much of it in his life, and so seeks out beauty. I’m a man who loves flowers, he said of himself, in sum. To me, he’s a fluid man. He doesn’t attach to much, but he’s not aloof either, just loose: he doesn’t get attached to things or ideas, nor does he probe much for meaning. He’s ready to be content with what is, though making sure that circumstances are opportune for contentment. Budd started out long ago, he told us, feeling his way towards his own interests through intuition and inspiration. In 1956, he saw a Rothko painting in a book, and in it he saw a way of living, and a way of making a living; he saw where he wanted to be, and then he got himself there. He’s ever since followed his intuition, and says he works on hunches. Today, if a hunch doesn’t pan out, he diverts route. With “too many loose ends in my brain”, he says, he doesn’t try to analyze what he’s doing, he just tries things out; if it’s not good, he moves on to the next thing.  Varty’s last question to Budd surprised me: he asked about the pink-tinted glasses Budd wears, who then explained: I don’t see well anymore, and I live in the desert where it’s really sunny. The rose tint reduces a large amount of glare, while protecting my eyes from bright sunlight, and they also provide sharper contrasts between objects so that I can see better. I know from glass artists that pink glass is the most expensive because pure gold is used to produce the pink hues; I also know from an anthropology major that the pink glass that was used in old cathedral stained glass windows was considered the highest spiritually, likely because of the cost to produce it, and so, used sparingly, it was tied to the most significant elements, often used to represent Mary. It occurs to me that Harold Budd sees the world, as the saying goes, through rose-coloured glasses. I think it perfectly applies to him, in every way—call it a hunch. PS: After the talk, I introduced myself to Harold and told him the story about my film. He was gracious to me, and amused by the story, and he kindly autographed the S-8 cover. He held my hand the whole time we talked. He's 79.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed