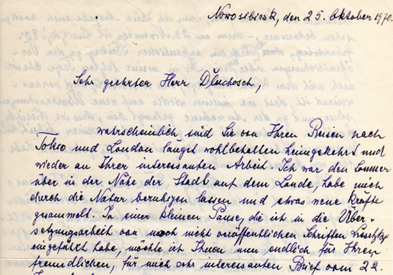

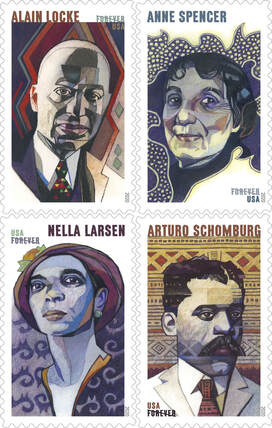

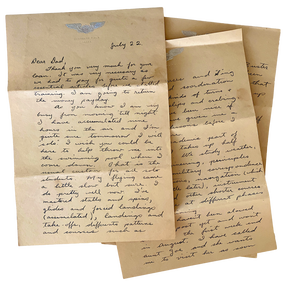

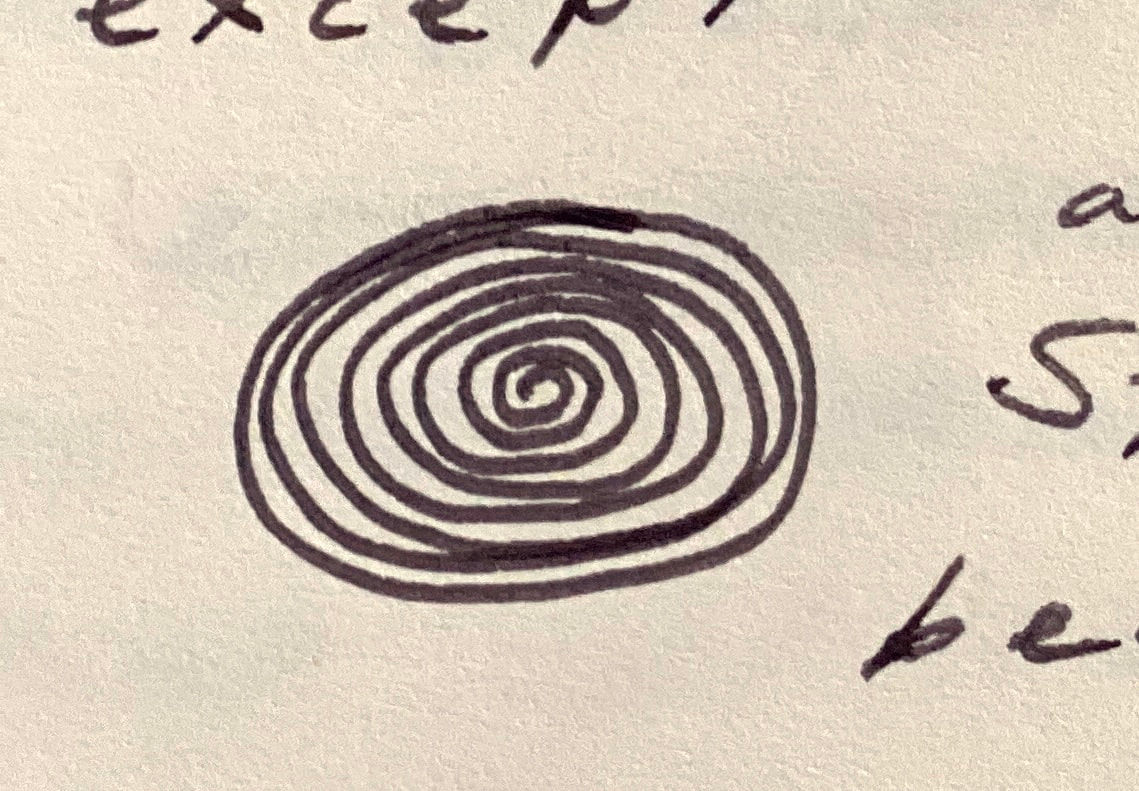

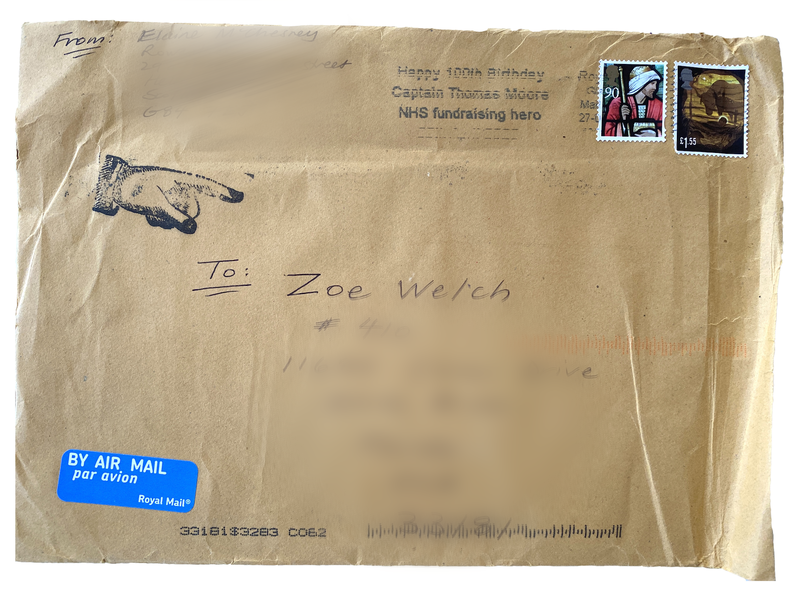

(For E. a letter-writer.) Don’t you want to pick that up? Turn the sheet over in your hands, hold it up to the light and see the glow through the page, feel the texture of the ink on the paper, sense the sender and the sendee, feel yourself carried through time to where this was, almost becoming the script, the scribe, and the go-between. I want to.  It looks like it's written on onionskin paper—a virtually sheer sheet, its lightness important during the days when airmail (called Par Avion at its inception in London in 1929) was costly and people economized on postage by using lightweight paper. I don’t know if I would be as inclined to want to handle and explore this letter if it were typewritten, to let it linger in my hands, its physicality the thing transmitting the fullness of its metaphysical dimensions. I might still want to read it as eagerly, but with so much sensorial promise gone, much of the personal would be too. Letter-writing gets short shrift these days, considered a relic at best, a waste of time at worst; it’s gone from something quintessential to something antiquated, something once consequential to something now condescended to—mostly. Retro is currently cool in culture – vinyl records (even reel-to-reel); 35mm cameras and Polaroids; rock band t-shirts; high-waisted pants; cocktails and shaker kits; even IG filtres – but letter-writing hasn’t made the cut. There’s not much to package and sell to the practitioners of longhand. Maybe that’s why. Lives are recorded in letters. And the life around those lives laces the written lines, forming cultural records that capture and reflect for us the more intimate portions of collective life as they play out in private spaces. Why else would letters like the one above join collections in public archives, libraries, and museums? Letters contribute to our public history. If you type “letters” into Harvard library’s special collections search engine, and then “image”, you get 9,655 hits. If you do the same for the New York Public Library you get 18,038. What will happen 20 years from now, and 50, and beyond that? Will we publish emails? Not likely. Most of us delete our emails, and few of us turn to the mode with the tenderness, time, and tenacity it takes to correspond by letter. And we’d have to pass along our passwords to someone so that our emails could eventually be retrieved. Who do you share your passwords with? In any case, when’s the last time you lingered over an email—made a pot of tea, and settled into a comfy chair to read, and reread an email? Some don’t even use email anymore, or never really have, it too relegated to a generational joke. You know what I mean. I recently described to a millennial the functional hiccup I encountered on a website, and she suggested that it was probably because I’m “old” (she used air quotes), rather than considering for a moment that the platform and its navigation might be poorly designed and/or have had a glitch. It took everything in me to not roll my eyes and tell her that I’ve been using computers for longer than she’s been alive; that, apparently, though the web may be wide, her use of it as a conduit to the world seems to be pretty narrow, and narrowing. Ask Nick Cave about the power of a letter. No, wait, don’t—instead, listen to his 2001 ballad, Love Letter, an incarnation of the plaintive ache his composition is meant to remedy: Love Letter, love letter / Go get her, go get her / Love Letter, love letter / Go tell her, go tell her. What more is there to know about the potency of a letter? For the curious, the kindred, and the quixotic, letters also come bound and published as collections. I’ve read the collected correspondence between Al Purdy and Margaret Laurence, and between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz; next on my list is the published collection between Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark as well as the letters of Earnest Hemingway. I’m a letter-writer, which you’ve probably already figured out. I have a long history with letter-writing as well. My practice has always been the long letter, long in time to write which yields a letter long in pages. I’ll write over the course of a month or so. By the time I wrap it up, my sendee has accompanied me along multiple storylines in my life, the letter taking on narrative momentum a bit like a script might, but without the formal constraints of the three-act structure, resembling something more akin to Richard Linklater’s 2014 film, Boyhood, another manifestation of the filmmaker’s question: how do we cope with time passing? (Some letters help track what might offer answers to that question, or at least shed some light.) A storyline of mine, in a letter, might come to its conclusion within the span of the letter, or in the next one. Andrei Tarkovsky, another filmmaker whose work has expanded filmic language, wrote about his work and his aims as an artist in Sculpting in Time, describing film’s particular capacity to express the course of time within the frame. Letters do that too. I’m also into stamps, though I’m not a stamp collector. I always look forward to renewing my stash of stamps, making my selection based on the artistry and the message, little pieces of art I then send across the world. Right now I have round ones with chrysanthemums for international postage (there’s not a wide selection for international), a set of Voices of the Harlem Renaissance for domestic, and a set of coral reefs for postcards. It’s amazing how much there is to choose from—something to suit a range of tastes and interests. Do you remember Fargo? (The Coen brothers' film, not the series.) In it, running on a very minor plotline, Police Chief Marge Gunderson’s husband, Norm, is working on a painting for his submission to the federal duck stamp contest. It’s a thing. (Norm’s mallard earns him second place on the 3-cent stamp, a disappointment to be sure. No one uses the 3-cent stamp, he tells Marge. Of course they do, she replies, ever the pragmatic optimist and loving wife, whenever they raise the postage, people need the little stamps.) The duck stamp contest was started by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 as part of a conservation effort to protect wetlands and wildlife habitat, and it continues today. Conservationists buy duck stamps, knowing that 98% of the cost goes directly to protection work. Stamp collectors buy them to help increase their value, thereby increasing the returns to the intended conservation work. My first letters were written to my parents. To my father who lived far away from me as I grew up, and then to my mom, once I moved away from home. I love my father’s handwriting. It carries the same verve as the poems he wrote. I love my mother’s handwriting too. Once we began corresponding regularly I noticed that the W of my signature was very much like hers—a graceful line elongating the arc of the final curve. Over time I noticed how the way I wrote all of my last name had almost completely taken on the shape of hers—the looping lines drawing out the direct link of my lineage. To this day, I think of her each time I sign something by hand. And whenever I open the box where I keep the collection of our letters and cards to each other, our bond is illustrated in the assemblage of envelopes addressed to and from the same name, in the same script. After each of my parents died, I travelled to their cities to handle arrangements. This included going through their belongings, a strange and singular experience that mixes the past with the present, leading us to sometimes stumble onto secrets that might make sense of partial memories, and of family lore, helping to solidify one’s place and history, or at least to help illuminate it. My parents separated when I was an infant, yet I found letters between them dating from their separation to the time of their deaths. They wrote to each other as my parents, discussing me as I was growing through the stages of my life; and they wrote to each other as friends, across so much time and distance, and the troubles they each had. I found letters other people had written to them. And I found letters I’d written them. They’d each kept the letters.  Piecing everything together, I pieced together parts of my life I’d forgotten, with others I’d never known—some telling about me, some telling about the times. In it all, I learned more about myself, about them, and about their worlds. My mom wrote about the founding of Greenpeace, which was around the corner from us on W. 4th in Vancouver, and was where she volunteered. My father wrote about Mickey Munday, Miami’s Cocaine Cowboy pilot who lived down the street. And in a letter from my father to his, written when he 16 and in his first months of pilot training, I see in my father's maturing script hints of a  sterner man in my grandfather than any family story has ever told. It was the early 40s at the Randolph airfield in Texas and my father's attempt to fly for the air force an act of love on the part of a son for his father, an esteemed WWI pilot. The letter is written before my father failed pilot training. When I returned to Montreal from Miami where I’d gone to attend my father’s memorial, a postcard from him arrived in the mail. Postcards are often slower to make their way through the postal system, so it’s hard to know how close to his death he was when he wrote that card and mailed it to me. Included in the things I brought back with me from Miami was his suicide note, it in the same handwriting that swept across the postcard. I still have both.  Right now, I owe E. a letter. We’ve maintained our friendship through letters for longer than we’ve been friends in the same city. Occasionally we intersperse our correspondence with phone calls, and the rare text message, but it’s mostly our letters that hold us close. We send all kinds of things to each other in our letters. My last letter included several How-To Haiku zines I made so that E. and her Glaswegian pals could have a haiku-writing party together. Her most recent letter to me included a page torn from a small Muscat de Rivesaltes notepad, which I use as a bookmark (yes, I read physical books too ) and which I know she sent because she knows I love Muscat—it’s her promise to me that when we’re together next, we’ll go to her house in France where we’ll drink Muscat in the garden. Her letter also contained a little drawing illustrating something she was trying to describe to me about the nature of time. The illustration depicts E.’s woven Kabyle tray on the table beside her, it illustrating her point about time. There’s also the envelope, with its acknowledgement of Captain Sir Thomas Moore, the centenarian who started walking laps in his garden on April 6 to raise money for the UK’s National Health Service efforts to confront COVID (by the end of the day on April 30 – his birthday – his efforts yielded £32.79 million). And, finally, the Par Avion sticker there to remind us that this thing is not travelling to me by boat. Since the COVID lockdown, I also received a thank-you card from Our Community Bikes, one of my favorite not-for-profits in Vancouver. Working under the pressures this lockdown has caused so many, they held a fundraising campaign to which I contributed. They sent me this handwritten  thank-you card, mailed inside a hand-addressed envelope. No Avery type-printed address stickers for Our Community Bikes, and so none for me. For a while I was pen-pals with a woman in a Los Angeles maximum security prison. She was the mother of three, and was in under the 1994 three-strikes-you’re-out law. Her infractions were minor drug-related charges and traffic stops gone wrong. She was doing life.  For a few years in my early 20s I had a PO box at the main post office in downtown Vancouver, even though I had home addresses everywhere I lived at the time. (I once gave my PO Box address to a guy who asked for my phone number, telling him, cryptically, it was the best way to reach me, no matter what.) I loved picking up mail late at night, entering the quiet alcove of the post office, eyeing the others doing the same. Did they too have street addresses like me? I fell in love once through letters. We met at a conference in Banff, and then discovered that we lived 2,300 miles apart. And so when we each returned to where we lived, he to his small house on the Anzac reserve in northern Alberta and me to my brownstone walkup on the Montreal plateau, our courtship began by letter. He wrote in pencil, he explained in his first letter, because it’s more forgiving. And with that I was hooked. I once wrote a letter to my sister in New Zealand, and was so keen to be close to her that I photographed the pages and emailed them to her. And once, I wrote a letter to E. in Scotland, and photographed the pages to keep for myself, printing them out and pasting them into my writing journal to mine for ideas later. Years ago, in the wake of my parents’ deaths, I wrote often to L., my closest friend far away, who later told me and tells me still: I have all your letters. When you’re ready, they’re yours. I haven’t asked for them yet. Today, I’m a museum educator and I work a lot with senior high school students. No matter the project, I ask them to explore their ideas with a pen and paper because the brain behaves differently that way. When writing longhand, neural activity is triggered in particular ways—all good for cognition and creating. The field of research known as “haptics,” which includes the interactions of touch, hand movements, and brain function, tells us that cursive writing helps train the brain to integrate visual and tactile information, and fine motor dexterity. So, it’s spatial, cognitive, and kinetic. Other research highlights the hand's unique relationship with the brain when it comes to composing thoughts and ideas: a material activity, and slower than typing, handwriting forces us to rephrase ideas and concepts in our own words. So when I ask students to write by hand, they’re making sense of their learning, and their world, in their own voice. Additionally, the process of production that handwriting involves, each letter formed component stroke by component stroke, recruits neural pathways in the brain that go near and through parts that manage emotion. All this making learning both stickier and more holistic. These benefits are aren’t just for young brains. Neuroplasticity belongs to us all. We each have the capacity to continually change our brain’s architecture and operating system (neurons that fire together wire together). And it’s not just writing longhand that enhances positive neural rewiring—reading longhand does too. When we read handwriting, we activate the same neurological instructions required to write those same letters and words, something keyboard-written type doesn’t demand of us. So, basically, to read handwriting is to be empathetic. There’s also a heap of research on attention: how much, how long, and how deep our attention is when we read online versus reading something in our hands. It turns out that deep reading – the process of thoughtful and deliberate reading through which we actively work to critically contemplate, understand, and ultimately enjoy a text – is compromised when we read on a screen. When we skim and scan a lot, and surf from hyperlink to hyperlink, our brains get good at skimming and scanning and surfing – to the brain, all shallow activities – and less good at neurological deep diving, the kind of brain capacity required for concentration, contemplation, and reflection. So, as we reroute our neural pathways online, we are remaking ourselves in the image of the internet—the medium is indeed the message. I remember a day in 1996 when I gazed for a long time at one of the first advertisements for a wireless phone. The billboard presented the image of a pristine conifer forest, sunrays filtering through the grove of trees, with the words finally free plastered across the tree tops and reaching into the sky--two little words redefining the concept of being untethered (just two of the many that have grown into the barrage of lexiconic gaslighting we have today). Alternate facts, indeed. These days, more than 20 years since that ad came out, in an attempt to simultaneously unplug and reconnect, people now pay to attend forest bathing workshops in groups that are led by somebody who asks that phones be turned off.

There are tangible costs and consequences to those today who choose to opt out or who limit their participation in the online world. From being mocked and called a Luddite (go read about the Luddites, they’re pretty interesting), because, apparently, it’s unchill to step away from monolithic click-bait corporations instead of capitulating to the transactional interests of their opaque business models (like FB [uber uncool] and its millennial-pacification do-over, IG); to more culturally ubiquitous and coercive expectations, silent and tacit, that you must migrate your life online to work in today’s economy (think LinkedIn), even if your work takes place off-line. It’s not called the attention economy for nothing. I don’t want to go fast and break things. I don’t want to lean in. I don't want to curate my life, and pin it. I don't want to follow influencers. I don’t want to read Toni Morrison on a backlit screen. I don’t want to use performative platforms to maintain my powerful friendships, especially when a long stretch of Earth keeps from us being together in person. I don’t want market-driven algorithms driving my information, my attention, and me. I’m not a consumer of content, I’m a sentient being, animated by caring, curiosity, and concerns of all kinds. I’m not a content creator (a stunning piece of language that so baldly reveals the vacuity of the enterprise), cranking out filler for the spaces between the ads. I’m an artist. I’m an agent. A citizen. I choose analogue channels. I choose digital channels. I choose. I wonder about those who don’t write by hand anymore, and those who don’t correspond by letter. In a world absent of handwriting, and where no one writes letters anymore, there’s an empty mailbox, an empty archive, and what more? It would seem there’s a lot to lose when we put down the pen. We lose connection, we lose our unique dimensionality, it looks like we're going to lose pieces of our histories both personal and public, and, apparently, we’re losing our minds. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees. Maybe experiencing forests by paying someone who first tells you to turn off your phone while you’re there is a good sign that there’s a system glitch, a big one. I’ll check the mail later. I always know when it arrives. The postman on this route talks on the phone all the time. He has on a headset but he’s loud. I can even hear him when he’s driving up and down the street, his cheerful holler blasting from the open truck doors. But for the moment, I’m going to go inside and type this up. (You knew I was writing this by hand, didn’t you?) I wish there was a way for your read it as it is. Not this time. PS: I was prompted to write this essay for work. While the museum remains closed, we’re all pitching in to produce virtual experiences, including writing pieces for the blog. With the threat to the US Postal Service on my mind, I offered to write something about letters. Writing on commission is unusual for me. I loved working with a gifted editor, and was interested to see how and where my personal voice had to conform to an identity other than my own. Here's the version of this piece that went up on the museum’s blog. It’s pretty different. (And, no surprise, the blog version is a lot shorter—I was told that people just don’t want to read anything too long. So, the dictates of the medium do indeed dictate the message.)

1 Comment

I've crouched in a corner hiding from an imaginary shooter twice in my life.

The first time was when my son was 10. We went to a birthday party for one of his friends that included playing laser tag at a local outfit. There, strapped into a bleeping vest, I ran through the black maze in the dark trying to dodge everyone else in their bleeping vests, and I was terrified. The experience of feeling stalked, even by a 10 year old holding a play gun that emits beams of light, was so traumatizing that I found a corner where I crouched, knees up in front my vest to hide its blinking lights, hoping nobody would find me while I waited for the game to end. The next time I crouched in a corner to hide from a shooter was not voluntary. I lead a museum program that takes me into ten senior high schools in Miami-Dade County each year. I'm currently winding things down for this edition and am visiting the classrooms for our feedback sessions. This afternoon, I happened to be in a school when a Code Red drill started. This is when students and teachers put into action the training they've been given in the case of an active shooter at their school. From one instant to the next, a calm conversation with the kids was blasted by a loud buzzer and suddenly the teacher was up and crossing the classroom floor to turn off the lights, lock the classroom door, and close the blinds that give onto the hallway. Simultaneously the students moved en masse into a corner of the classroom away from the door and windows where they crouched under desks. I had no idea what was going on so I did the same thing: I hunched under a desk alongside 20 students and their teacher. I asked the 17-year old girl beside me what was happening and she whispered back, a Code Red practice, and then had to explain to me what that meant. (I moved to Miami from Canada and am still learning about this place.) Glancing around me from there under that desk, I noticed several of the juniors were wearing what were clearly school-issued t-shirts with the caption, Graduation Class 2020. And there, hiding in a dark corner with all these kids, as I stared at their shirts in the long shadow of the Parkland school shooting just a year ago, all I could think to myself was, not at this rate.  We girls all wore brown pleated pinafores, the kind with a bib and a belt that cinched at the waist with a metal buckle. Beneath it was a crisp golden cotton button-up shirt. It must have been cheap cotton, something poorly woven or starched to hold its structure, because it slightly scratched at my skin below. In the winter we worn brown leotards, and the rest of the year brown knee-high socks. My mom dyed a batch of my underwear to match the colour of my pinafore, completing the uniform and my adherence to it. I wore them over my regular underwear, turning the outer pair into something more akin to tiny pants under my skirt, part of the uniform; so when I hung upside down on the monkey bars with my belt undone and my pinafore falling inside-out over my head toward the ground, I didn’t think I was doing anything improper. I wonder if my mom was required to make that undergarment for me, or if she took the initiative on her own—a small gesture toward ensuring I fit in. Probably. All for a little private school a few blocks away from where I lived at that time. It was actually a three-storey house, a mansion refitted as a school. This was not a school for the elite. There were no preening parents conscientious about our grooming. No chauffeurs gliding up to the curb; no nannies clasping the little hands of their charges. We were the opposite. We were the children of single parents: those separated and possibly divorced, some probably widowed, and some maybe never having been married at all. It was a time when no one spoke about these things. They were connections we would figure out later, looking back. When the school day was over, we stayed, supervised as we played in the large yard until we were each picked up by a parent to go home. It was the only school with such a service then. It was a good school. Small classes. Boys and girls comingling on the playground, something unheard of at the time. We had French lessons and made our own butter, slowing churning cream by turning our mason jars each afternoon, end over end, our little hands clutching carefully so the glass wouldn’t slip and break, destroying our alchemy before the magic took hold. After each churning session we set our jars on the windowsills in the autumn chill outside, our names in childish script identifying whose was whose. Through the pane, there was mine, Elizabeth looping across the label, the contents well on its way to becoming solid. I attended grades one and two at this school, and did very well. I loved school and school loved me back—my marks were good then, and I felt proud of my work. Then came the antonym test: words stacked in one column on the left side of a sheet of paper had to be matched with their antonyms on the right side. It was my job to do the matching. Across from rough, I wrote calm. When my test was returned to me, calm was crossed out in red ink and smooth was inserted in its place. I lost points. All six years of me was incensed. From summers spent with my cousins at their family cottage beside a lake, where all the older kids waterskied and everyone would squint at the water each morning to see if the surface was flat and good for the first spin of the day, I knew for a fact that the opposite of rough was calm. When the water is calm, we waterski; when it’s rough, we don’t. Still too little to ski myself, I was the spotter in the boat. I watched the waterskiers to keep them safe, eyeing the waves for all signs of threat. I knew water and I knew its surface. All us kids did. _________________________________ Ellen Langer tells a good story, one I wish I’d heard when I was six and I knew that the opposite of rough is calm. Langer is a Harvard social psychologist. Much of her research looks at how our experiences are formed, perceived, received, and understood by the words we attach to them. Langer talks about questioning assumptions, examining common axioms that come to dominate our perceptions and precepts and dictate how we frame knowledge. Make no assumptions, Langer says, or at least be aware of the assumptions with which you operate. Things aren’t always what they seem, nor are they always what we think they are. Langer gives examples. Good ones. Simple. Clear. Effective. Empowering. Examples like this: if you take one piece of gum, put it in your mouth, and start chewing, and then you take one more piece of gum and add it to the one you’re already chewing, you still have one piece of gum in your mouth. If you have one pile of laundry on the floor and you then add one more pile of laundry to it, you still have one pile of laundry. 1 + 1 = 1. The opposite of rough is calm. _________________________________ At six years old, I was the victim of epistemic injustice, I know that now. Epistemic injustice is the act of wronging someone in their capacity as a knower. The term was coined by Miranda Fricker, Presidential Professor of Philosophy at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Epistemic injustice straddles the fields of philosophy (ethics in particular) and epistemology, looking at the construct that is knowledge. In broad terms, it’s concerned with how social power operates and how it’s attributed to individuals and groups, particularly through the many lenses of the official story: empire and post-colonialism; gender; race; economics—basically looking at anything humans get up to—ultimately, examining who gets to define reality. When applied to the operations of education, epistemic injustice looks at the meta: academe and the cannon; and at the macro, in the classroom, concerned with the power dynamics at play between teacher and learner. Epistemic injustice reminds us to consider who gets to decide what’s the opposite of rough. _________________________________ I work with high school kids now. I’m not a teacher. I lead a project that takes me into several high schools each year, involving hundreds of students. I tell the kids in each class about my six year old self knowing that calm is the opposite of rough. I share Langer’s examples of gum and laundry. Because I know about epistemic injustice, I make a point of doing so. I want them to know that 1 + 1 can = 1 The last time I did, I noticed a quiet kid at the back of the room. Long and lanky, his body stretched well past what his chair could accommodate. As I was talking, I saw a curl appearing on his lips, his eyes brightening as his eyebrows gradually lifting higher on his forehead; and as he slowly began to speak I saw illumination emanating from all over him. Wow, he said, you’re blowing my mind right now. Yes, I thought to myself, Blow your mind wide open. And please try to keep it that way. Oh, one last thing, I said as I was getting ready to leave, life can be rough, so try to take it calm and smooth. All the kids smiled. |

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed