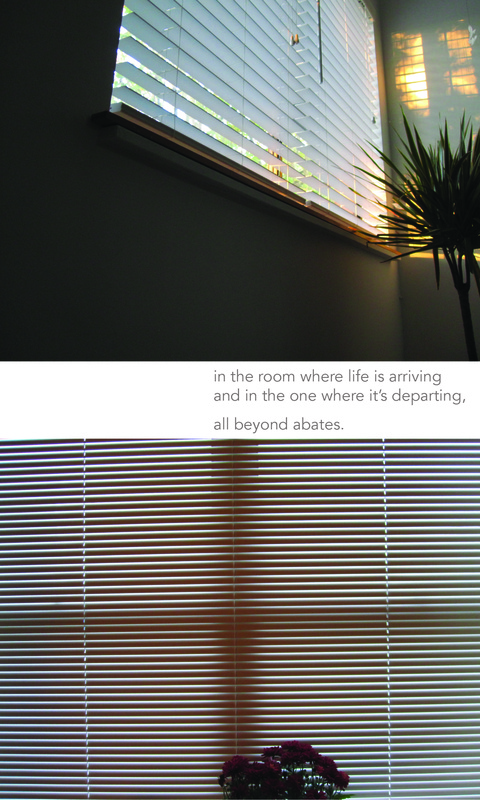

February 14, 2022 Thirty years ago today I was blowing the smoke from my contraband Marlboro into the frigid night through the narrow opening between the window frame and its window, the cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other. I was visiting L in Charlottetown and we’d gone out to the country house that a friend of hers had lent us for a few days. I was on the mend from a recent break up, and still lingered in the territory we occupy after a loved one takes their life, in my case my father ten months earlier. Two days later I was back in Montreal and a day after that my son was at a sleep-over I’d planned so I could go see Primal Scream at Club Soda. But in the grips of loss I’d changed my mind and I was lying on my couch watching Thelma and Louise instead, letting my concert ticket go to waste. Part way through the movie, two police officers were at my door with the news. I let them in and they sat across from me, not far from the frozen movie frame paused on the tv screen. I didn’t want them to think I was shallow for watching this fugitive women caper commentary. It was before the internet and cell phones, so who knows how they found me. Police work. They were there to tell me that my mother had been found dead in her Vancouver apartment. Suicide. Valentine’s Day. I apologized to them for having to come out on a cold night to deliver such news to someone.  A decade later I was married for a time and Valentine’s Day was fraught for him, on behalf of me. Somewhere in the mid 2010s he thought we ought to embrace the day, in my Mom’s honour. And so started the tradition of going to a big hotel bar for a drink on each Valentine’s. Which is what I’m doing today. The 30th anniversary of her death. My mom lived with mental illness. Both my parents did. She raised me on her own, living on social assistance with the support of an exceptionally kind social worker. We lived in tiny one-bedroom apartments near Vancouver’s Kitsilano Beach (a fiscal hallucination now), me with the bedroom because she believed I needed privacy. She slept in the living room, first on a hideaway bed, and later, in a slightly bigger one-bedroom apartment, on a single bed pushed into a corner in the living room. When I moved out at 17 she moved into a bachelor apartment in a building for out-patients. There, we found another corner for her single bed, positioning it in such a way as to create a living area that felt separate from where she slept. On her birthdays I would offer to either clean her apartment (though she was pretty tidy) and make dinner, or take her out. She always chose out. Who wouldn’t. Sometimes we went to Vancouver’s Four Seasons Hotel lobby bar, or the one at Hotel Georgia. Of course we were way out of our price range, which was part of the fun.  The husband is long gone, but not my Valentine’s Day hotel bar tradition. My mom would love it. So would my father. (I eat a donut on his birthday because he loved going to his local Krispy Kreme in Miami where he chatted up everyone seated at the counter with their snacks.) I love this tradition. I feel so much closeness with my mom on this day, doing this thing. I can feel our silly thrill as I sit amidst the tonier well-to-do. Since 2011 when I became single again, I often invite a friend or two to join me on my tab. Until 2016 that was in Vancouver. From 2017-2021 I was in Miami for it. Today I’m doing it in Montreal — a first — and I’m on my own. For thirty years, I’ve been pretty quiet about my parents’ health, and even more so about their deaths. Close friends know. It’s a big thing to grapple with and I don’t want to freak anyone out. I’m fine (now), but strangers might not be. I’ve been especially quiet in my work environments. People are judgey — even if we're not supposed to be anymore — because, let's face it, diversity, equity, inclusion, and access hasn't exactly landed yet. This kind of disclosure carries a lot of heft and can carry even more innuendo. And so it concerns me that people will make assumptions and draw even worse conclusions. Not so much about my parents, but about me. I worry that people might ascribe to me whatever stereotypes they’ve acquiesced to — you know, shadowy, shameful stuff that can be weaponized to tank a career — taking away from me what they imagine my parents lacked. I worry that they can’t see past what characterized my parents’ deaths to see the resilience that characterized their lives. And mine. This was my mother’s greatest wariness. It dogged her. And so today, on this 30th anniversary, I honor my mother’s life, and her death. And, I honor every minute in-between. In public. I wrote an ode to my Mom on another Mother's Day. You can read that one here.

0 Comments

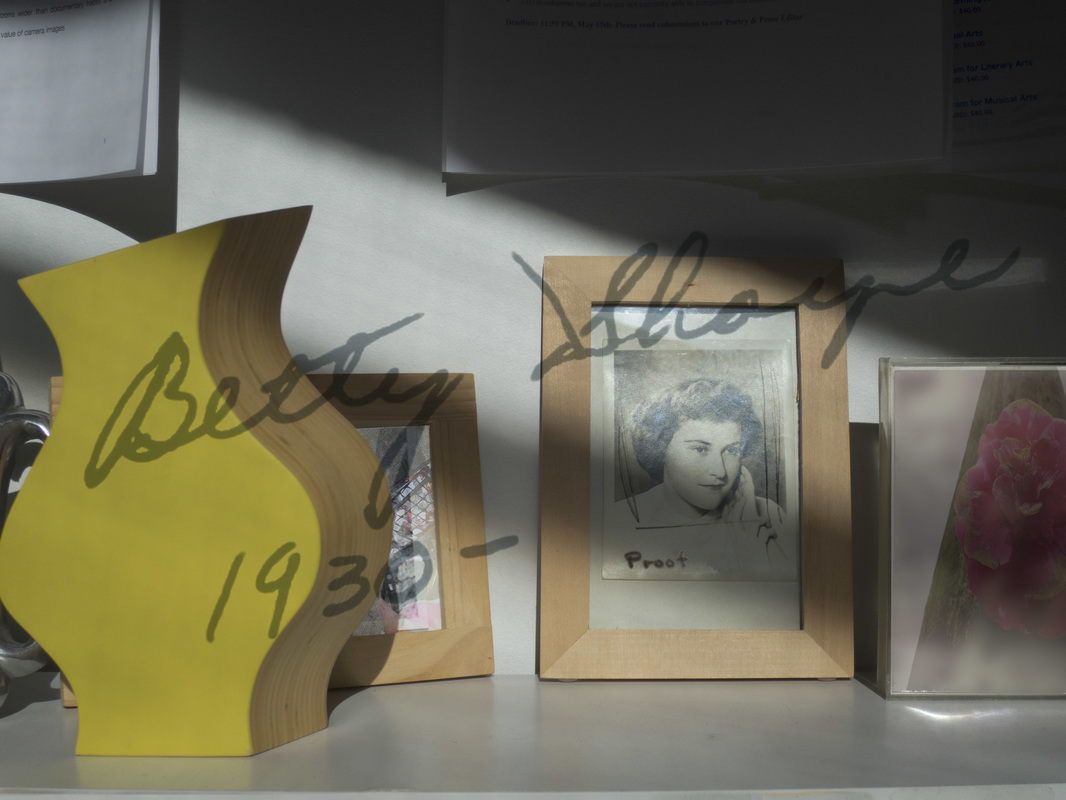

Inside a soft cardboard photo folder, the kind that people prop open on mantels and sideboards to display their loved ones in pictures that were often taken, or were back then, in the photography studio of big department stores, is set behind the 8 x 10 scalloped edge window a portrait of my mother. It’s the option she must have selected from the others taken during the sitting that day, which she wedged, loose, between the folder’s covers. On the back of the folder, in her distinct and sanguine script she’d written: Betty Sharpe 1930 -

That incomplete assertion is devastating. Her eagerness and expectation is in plain view; and what seems to be her bright view of herself, and of her future, is also equally evident: she has resolve; she’s looking forward, to everything it seems. Now, though, looking back, knowing what only the coroner and I know, I see her openness to what lay ahead far more ominous than optimistic. What was she thinking, I wonder? Who did she think would fill in the blank after that dash to complete her sentence? Of course, when that time came, when the end of that statement was upon us to record, she wouldn’t. And no one else did it in her stead either, which, today, obviously means me. I found this folder in a drawer as I went through my mother’s belongings after her death in 1992, when I was 30 and she was 61. I’d never seen the pictures before, I’d never seen the folder open on a mantel in someone’s living room; not in anyone’s, not anywhere, not ever. The set of pictures was taken in 1951, at Hudson’s Bay in downtown Vancouver, 10 years before I was born, before she knew my father, I think, but don’t know for sure. All those details – her life really – is a mystery to me, a story I piece together from snippets she shared offhandedly, where, I later learned, she was sometimes careful to cloak parts, offering a looser interpretation of her past than the truth on its own would convey; I piece in layers from my own memories, vague and few as they are, and also from conjecture; from what I know about things as a woman myself, now middle-aged, as a mother too, and from the kinds of experiences life delivers to some of us. Our life was lived in a perpetual present; there was no discernible past that was talked about, no family over visiting and telling tales, for they’d all but vanished, though not yet in the absolute as they would after everything, later. At that point, in these pictures, she was still a Sharpe, as she declares in her script. She would later become a Welch, and then I would come along and be one too. I prefer one of the proofs of her taken that day, and that’s what I now have on my desk in a frame that's too large for the picture. I love seeing the word proof written in wax pencil across her blouse, and the loose markings drawn around her face so long ago, tentatively seeking out the border that would compose this official portrayal of her, the tracings a kind of divining rod—I like seeing all that extra of her: her hands with their long fingers held delicately, and just so, the slopes of her shoulders, the light line of her pearls barely apparent, details about her not extraneous to me as I want to see more. Knowing her, she probably wouldn’t like my selection from the set, nor that I put the messy proof in an outsized frame on display. Yet, I also know that she would understand why I like it, and she would understand what I’m doing—and she’d be flattered, and pleased, and she’d approve anyway, despite her own opposition. She was generous that way, with a largesse of mind that made room for difference, probably because she knew from experience how much it mattered to give others room to live as they are; probably because she was given so little room herself, or, worse, sometimes finding herself locked inside a few. And I know her face, that placid, flat expanse of pretty features, would shift from feigned consternation into a relaxed form, yielding a slight nod and slighter grin, telling me it’s ok, telling me, in fact, that she likes the transgression. Subtle, yet seen, this look is something we shared between us. I think she always understood what I was doing. And I know she always approved. Though some boundaries were loose, and amorphous, and something that couldn’t always be observed, or enforced, or even noticed from the outside, there were other boundaries, inside, ones more important and enduring, that defined the particular territory we inhabited. It was sometimes random and sometimes raw, and it was sometimes rich in the ways that only those with less seem to know; ours was a singular life of mother and child, she weathered and me wild; it was an entirely original world, one I didn’t really see as unusual, and it’s one that’s lasted. So, after all, after everything, she is now on someone’s mantel. Proof. And I’m not filling in the blank after that dash. I’m keeping her life part of the present, still. I know she’d approve. Today is my father's birthday.

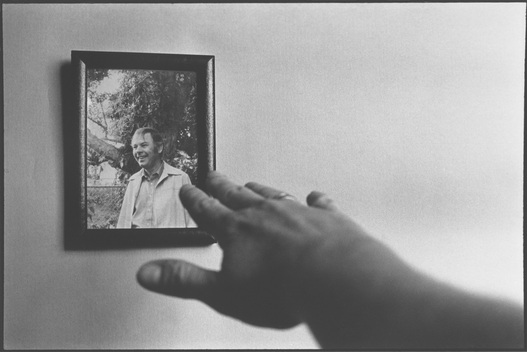

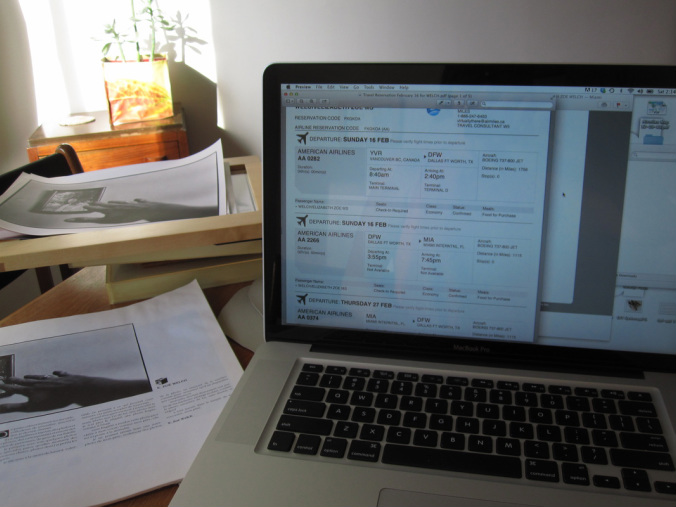

Martin Thomas Welch was born September 12, 1926. He would have been 88 years old today. At home in the US, he was known as Marty; when living in Canada he was known as Tom because he lived in Vancouver's Chinatown where people had trouble pronouncing Marty. In the unusual configuration that composes my family, as a child I sometimes referred to him as Papa Tom to distinguish between him and my foster father. In person, though, I always called him Daddy, even in adulthood. I often wondered why I continued with the childlike term Daddy - then, when returning to Miami last winter on a family pilgrimage I realized that everyone in my family refers to their father as Daddy - even my 92 year-old aunt. So, today, in honour of my father, I'm going out for donuts. Daddy loved going to Krispy Kreme on NE 167th St. in North Miami; there he made friends, paid for others though he was poor himself, and once brought a homeless woman to my Grammy's house to help the woman out. There's no Krispy Kreme in Vancouver so I'm going to a Tim Horton's. I think Daddy would approve. RIP Daddy. I miss you so much, and love your more. (PS: This photo was part of a piece I had published in the excellent photography magazine, Ciel Variable, automne 1991, a few months after Daddy's death; the image was accompanied by a poem I wrote entitled "mon père".) Last night super moon, summer in the city. Midnight was warm. Lush life, air itself. It was my Mom's birthday - she would have been 84. I want to lay my head down in God’s lap, or lie on Jesus’s couch safe in love. Instead, today I'll walk across the sand flats at Spanish Banks - it’s the lowest tide of the year, in concert with the super noon. My pilgrimage. I’m going to wear a silk shift that has a print of the ocean and sky on it, with a freighter on the horizon line. I’ll fit right in. And that's what I seek. Seamlessness. I'm at my YVR gate. I'm leaving for Miami, my first time back since my father's memorial in April 1991 after he took his own life. He was 64. I was 29. Ten months later my mother would take her's, but I didn't know that yet, not then.

|

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed