|

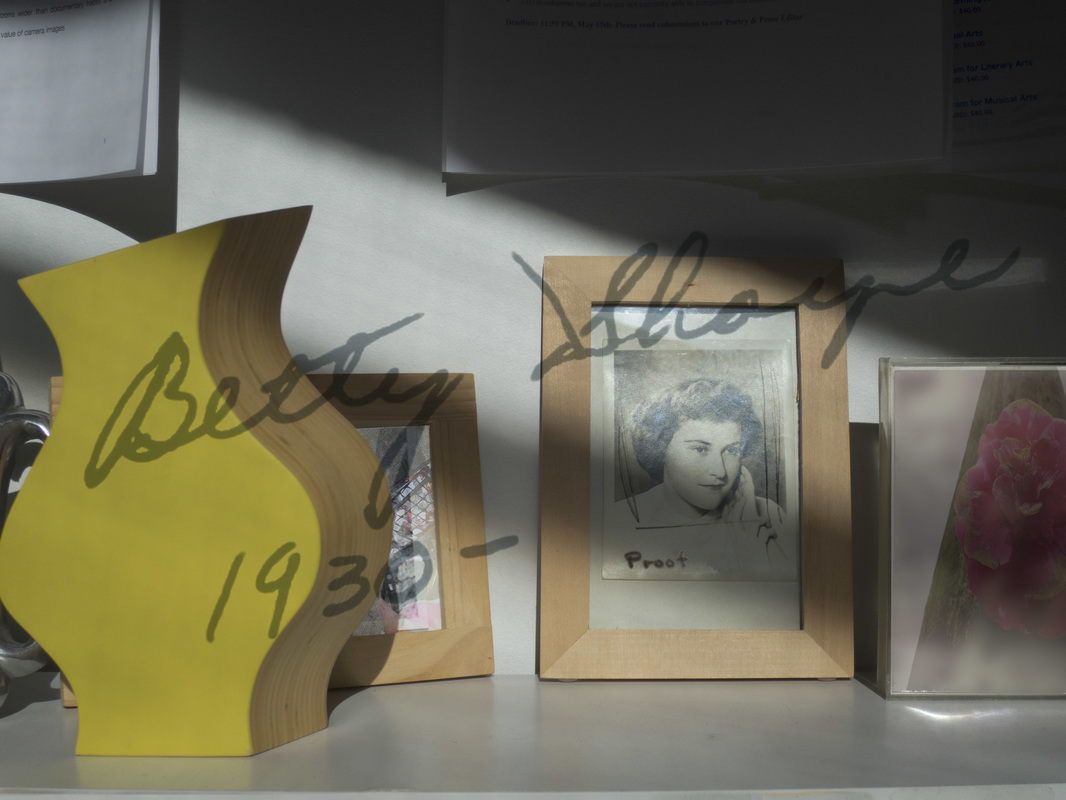

Inside a soft cardboard photo folder, the kind that people prop open on mantels and sideboards to display their loved ones in pictures that were often taken, or were back then, in the photography studio of big department stores, is set behind the 8 x 10 scalloped edge window a portrait of my mother. It’s the option she must have selected from the others taken during the sitting that day, which she wedged, loose, between the folder’s covers. On the back of the folder, in her distinct and sanguine script she’d written: Betty Sharpe 1930 -

That incomplete assertion is devastating. Her eagerness and expectation is in plain view; and what seems to be her bright view of herself, and of her future, is also equally evident: she has resolve; she’s looking forward, to everything it seems. Now, though, looking back, knowing what only the coroner and I know, I see her openness to what lay ahead far more ominous than optimistic. What was she thinking, I wonder? Who did she think would fill in the blank after that dash to complete her sentence? Of course, when that time came, when the end of that statement was upon us to record, she wouldn’t. And no one else did it in her stead either, which, today, obviously means me. I found this folder in a drawer as I went through my mother’s belongings after her death in 1992, when I was 30 and she was 61. I’d never seen the pictures before, I’d never seen the folder open on a mantel in someone’s living room; not in anyone’s, not anywhere, not ever. The set of pictures was taken in 1951, at Hudson’s Bay in downtown Vancouver, 10 years before I was born, before she knew my father, I think, but don’t know for sure. All those details – her life really – is a mystery to me, a story I piece together from snippets she shared offhandedly, where, I later learned, she was sometimes careful to cloak parts, offering a looser interpretation of her past than the truth on its own would convey; I piece in layers from my own memories, vague and few as they are, and also from conjecture; from what I know about things as a woman myself, now middle-aged, as a mother too, and from the kinds of experiences life delivers to some of us. Our life was lived in a perpetual present; there was no discernible past that was talked about, no family over visiting and telling tales, for they’d all but vanished, though not yet in the absolute as they would after everything, later. At that point, in these pictures, she was still a Sharpe, as she declares in her script. She would later become a Welch, and then I would come along and be one too. I prefer one of the proofs of her taken that day, and that’s what I now have on my desk in a frame that's too large for the picture. I love seeing the word proof written in wax pencil across her blouse, and the loose markings drawn around her face so long ago, tentatively seeking out the border that would compose this official portrayal of her, the tracings a kind of divining rod—I like seeing all that extra of her: her hands with their long fingers held delicately, and just so, the slopes of her shoulders, the light line of her pearls barely apparent, details about her not extraneous to me as I want to see more. Knowing her, she probably wouldn’t like my selection from the set, nor that I put the messy proof in an outsized frame on display. Yet, I also know that she would understand why I like it, and she would understand what I’m doing—and she’d be flattered, and pleased, and she’d approve anyway, despite her own opposition. She was generous that way, with a largesse of mind that made room for difference, probably because she knew from experience how much it mattered to give others room to live as they are; probably because she was given so little room herself, or, worse, sometimes finding herself locked inside a few. And I know her face, that placid, flat expanse of pretty features, would shift from feigned consternation into a relaxed form, yielding a slight nod and slighter grin, telling me it’s ok, telling me, in fact, that she likes the transgression. Subtle, yet seen, this look is something we shared between us. I think she always understood what I was doing. And I know she always approved. Though some boundaries were loose, and amorphous, and something that couldn’t always be observed, or enforced, or even noticed from the outside, there were other boundaries, inside, ones more important and enduring, that defined the particular territory we inhabited. It was sometimes random and sometimes raw, and it was sometimes rich in the ways that only those with less seem to know; ours was a singular life of mother and child, she weathered and me wild; it was an entirely original world, one I didn’t really see as unusual, and it’s one that’s lasted. So, after all, after everything, she is now on someone’s mantel. Proof. And I’m not filling in the blank after that dash. I’m keeping her life part of the present, still. I know she’d approve.

1 Comment

|

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed