|

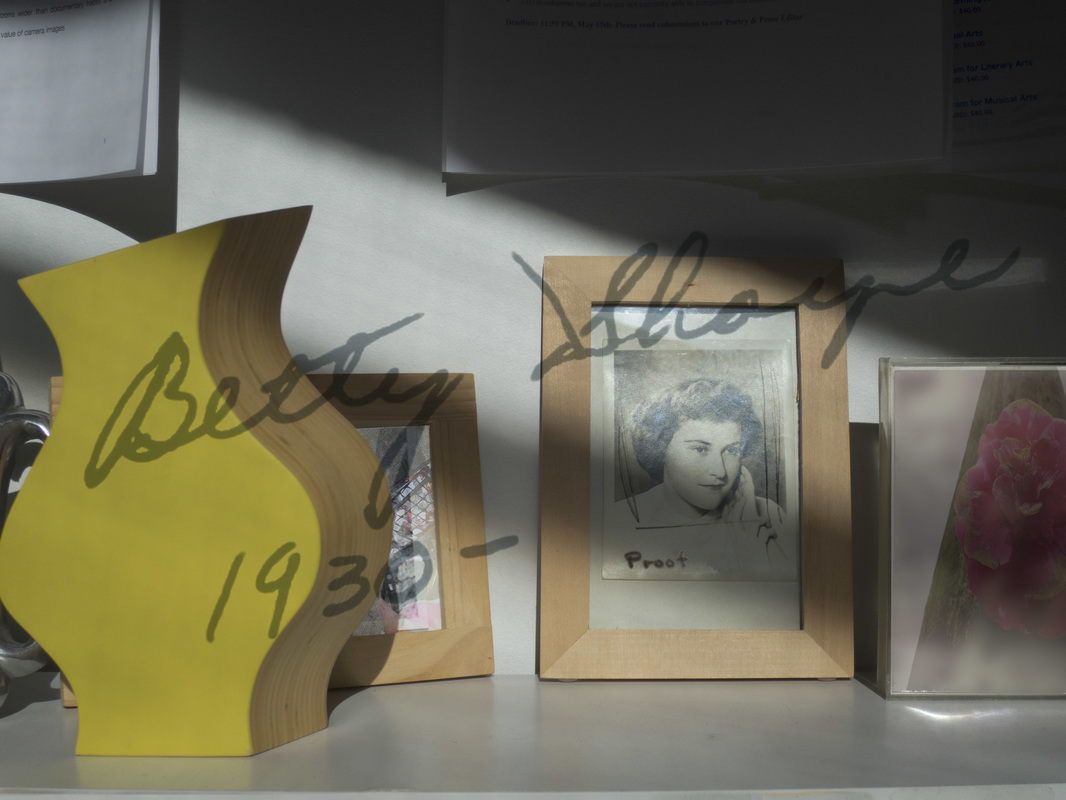

I have to confess to feeling pretty crushed. Maybe I should turn off the news, close the virtual pages of my online newspapers, close the curtains, close my eyes, tune out completely. Tuning out seems to be the direction I've taken to greater and lesser degrees in most dimensions of my life since returning to Montreal. So when I encounter warmth in something I take comfort.

I recently encountered warmth in details surely selected by their presenters for the quiet impact they offer to anyone attuned to detail — like me. Here are three little things that have recently heartened me:

I don’t know why the adage says, the devil’s in the details. I think I’m going to look for the angels in the details.

0 Comments

Fourteen months into the pandemic, I was waylaid by a lassitude I couldn’t kick. I had it bad — I couldn't even stay inside a novel because my capacity for deep and sustained focus was gone. Then I read Adam Grant’s 4/19/21 NYT opinion piece, There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing. Yup. That’s it. That’s me, I thought.

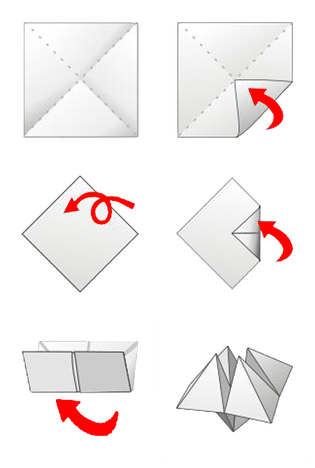

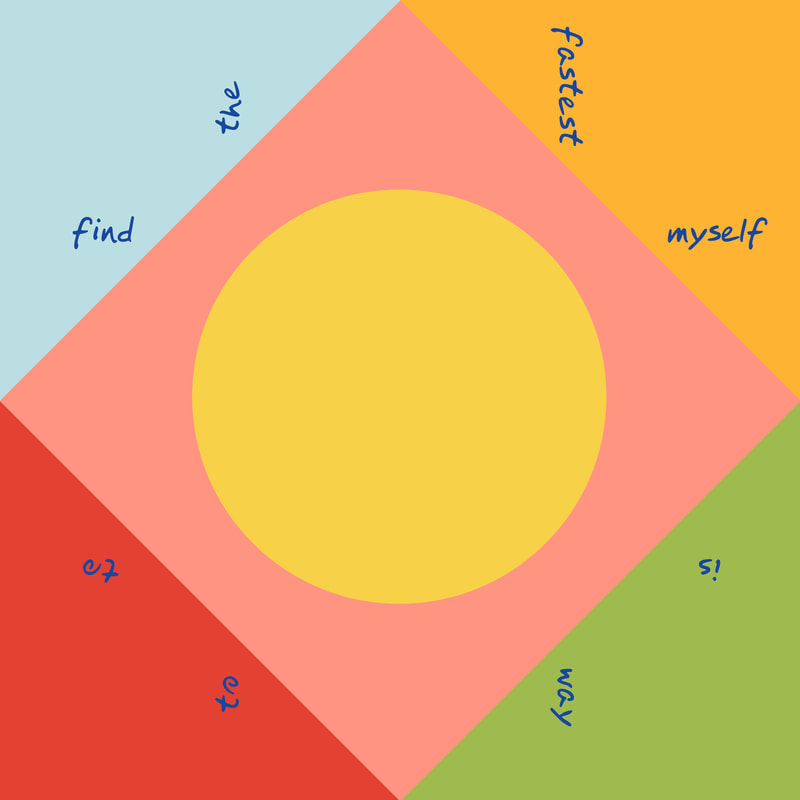

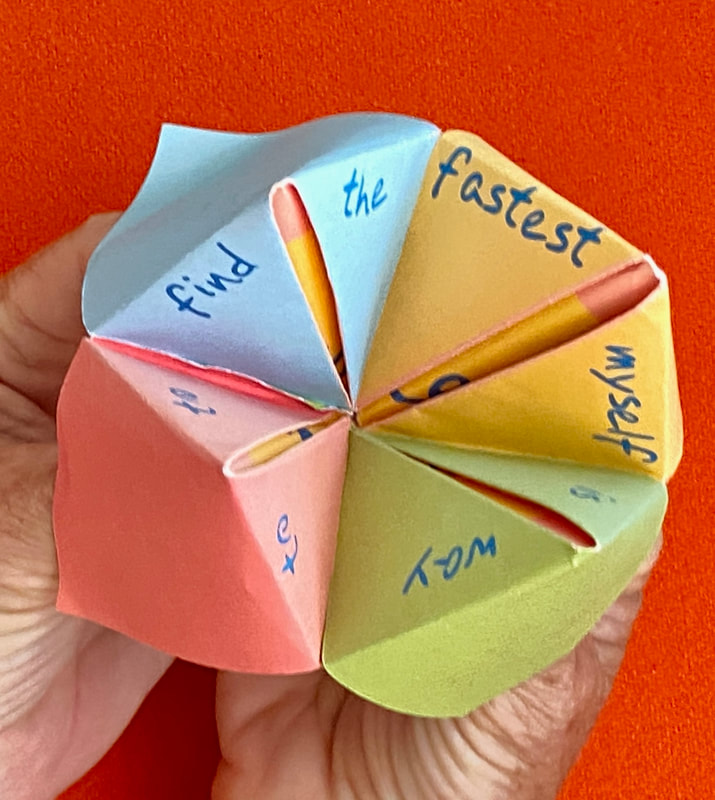

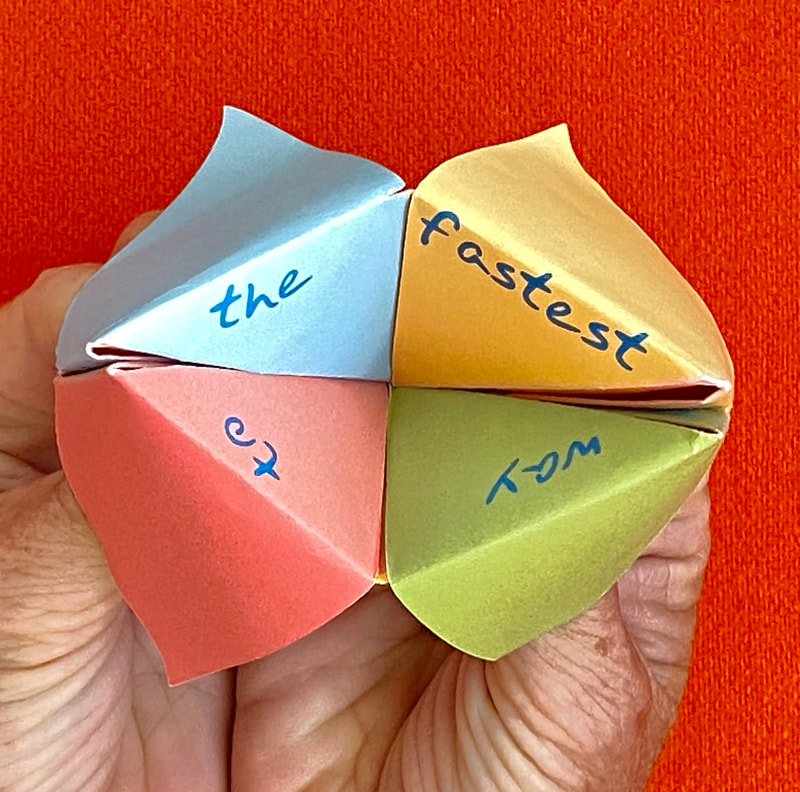

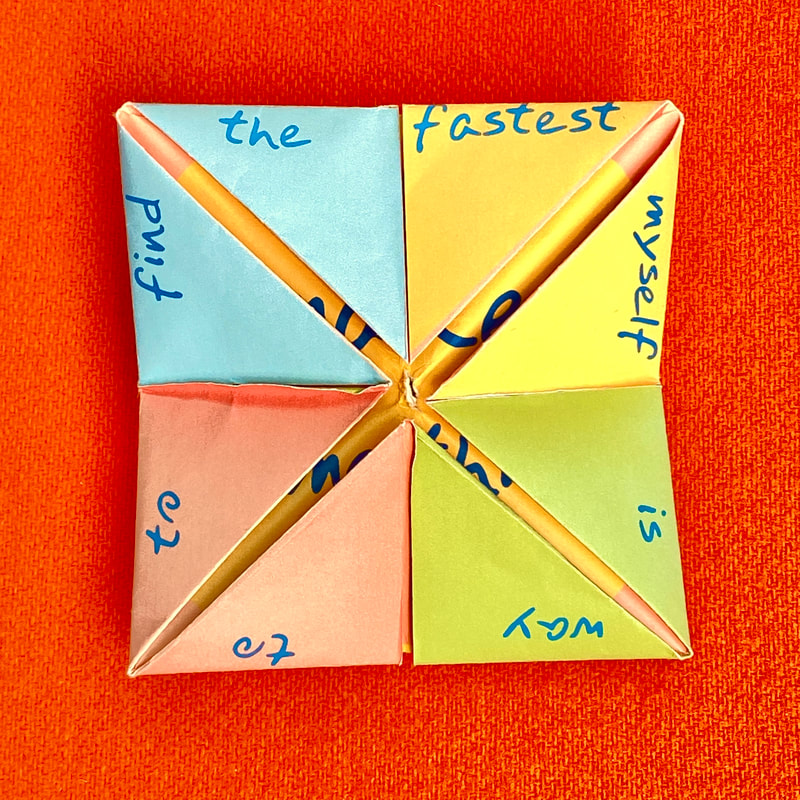

To get myself there, I went over to my work bench and fiddled with some paper, sticks, pens, glue, thread, and whatever else was laying around that day. Eventually, this is what I made. It has a lot of different names — fortune teller; chatterbox; coin-coin (in French) — whatever it’s called, here's the one I made as my gateway to getting out of languishing. It says: the fast way to find myself is to Then I answered my own question: the fast way to find myself is to For me, making something is a sure way out of a slump; to get myself out of languishing. It might be different for you. Try it out. Give it a whirl! Make one for yourself. And then answer the question: the fast way to find myself is to Here's how it works.  Take a square piece of paper and follow these folding instructions. Once folded, word by word, write on each of the 8 triangular tabs pointing down: 1 • the 2 • fastest 3 • way 4 • to 5 • find 6 • myself 7 • is 8 • to * you can use the photo below as a guide because the 8 words don't run in sequence Next, give some thought to how you would complete the statement. What does lead you back to yourself?

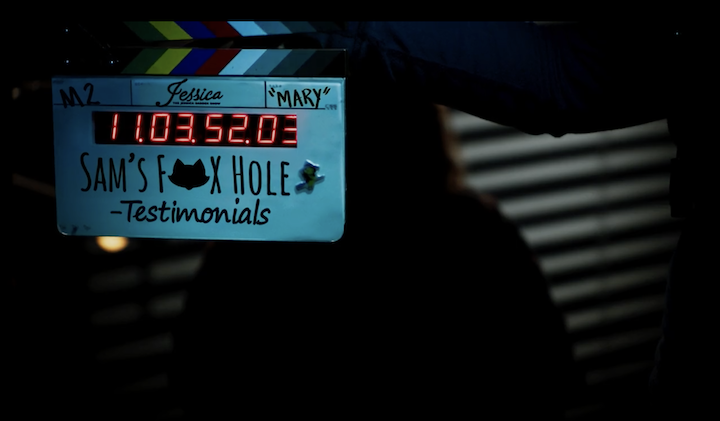

When you have your answer, open up the flaps and write it down on the inside. You can make as many as you like. You might find that your answer changes. Mine do. Yet each one is true. I save mine. I set them atop tables and windowsills around my apartment as friendly reminders. I’ve really taken this to heart. I keep this one – make something – on prominent view as a mindfulness touchpoint, to remind myself to notice how I’m feeling, and then, super helpfully, what I can do next. And you know what? It works every time. Its final season (S05) is soon ... well, soon for me. I'm waiting for the last episode to air April 25 and then I'm binging the whole thing. Till then, in no particular order, what I would ask Pamela Adlon, and Sam Fox. Wouldn't that be divine? A chat with Pamela Adlon. This piece contains spoilers ... Hello Pamela Aldon, Let's start by talking about food. Sam is a provider, but not just that. Sam is a nurturer, some of which she expresses through her cooking (she’s often in the kitchen making the most amazing meals and snacks). Does Sam see it that way? Does Sam see herself as a nurturer? Or is she just into cooking? And, Sam cooks a lot (a lot), and what she makes looks deliriously delicious. But, we almost never see her or anyone else eating all those meals she makes. What’s up with that? Dramatically-speaking, is there a difference between showing a cooking scene and an eating scene? Let's talk about music. The soundtrack across all 4 seasons is stellar, and often the lyrics replace dialogue—how does that come about? Do you discuss the script and intentions for dialogue with the music supervisor? Is there already dialogue in the script that gets replaced with song lyrics? The soundtrack is all over the map in terms of eras and genres, but there’s a through line—a consistent feeling. What is that for you? What’s the mood, the space, that you’re going for? Is it aligned with that the mood/space that the Fox family lives within? It all feels nostalgic and contemporary at the same time—or there’s a strain—again, a vibe, a feeling—that transcends time. This continuity seems to anchor to and through Sam: she is a woman of her time—whatever that time is. Let's talk about Sam Before what reads as a denouement in S04 E10, “Listen to the Roosters”, Sam seems to us to be experiencing some of the symptoms of peri-menopause, like her patchy pubic hair. As a middle-aged woman myself, I found this incredibly reassuring. It reminds me of a scene in Enough Said (Nicole Holofcener, 2013) when Julia Louis Dreyfus’ character discovers that her boyfriend, played by James Gandolfini, is missing a tooth—which she notices when they’re kissing. As she’s telling a friend about it she says she finds it sexy. Twenty years after a bike accident, I had to have a tooth pulled, and have since walked around with a gap in my mouth—Holofcener’s scene reassured me in the same way as yours did. Some would probably characterize this disclosure about Sam—patchy pubic hair loss, discussing this facet of (female) middle-aging—as brave. Is it? And who is it, at the end of the day, who’s brave? Sam? Or, Pamela? Does Sam has boundary issues, or has she chosen radical transparency? Let's talk about being a Woman Who is Sam as a woman? Particularly in this culture, and even more particularly in the context of LA. How does she perceive herself on the femininity continuum and within the social strictures that dominate how we define and perceive woman along that measurement. It strikes me that the two filmic storylines that helped me feel comfortable about intimate (sort of female) “frailties” “losses” “shortcomings”—yours about pubic hair and Holofcener’s about a missing tooth—are both told by woman. Do you think, ultimately, women are more forgiving, more accepting, of our bodily foibles, if not achieving equanimity then at least acquiescence? (Even though women are more relentlessly put upon to perform beauty and perfection in a particular way.) OK. Now let's talk about Motherhood. Is Sam a good mother? Does she think she is? Do her kids think she is? In S02E04 Max exclaims to her mother “you didn’t do anything that a mother does”, and after some back-and-forth about the issue Sam exclaims back, “you’re right, I’m a shitty mother”. But Sam is holding back so much in that scene. Sam holds back so much from Max (and all her daughters) about their father’s shortcomings and the complicated strings that push and pull outside the view of children. And that is what a mother does. Including not rescuing her own reputation in the eyes of her children at the expense of the father’s. Do the girls really know this deep down? What about Phil? Was she a good mother to Sam when Sam was a girl? These days Phil is somewhere between a bit “off” and totally unhinged, and Sam (appropriately) has a bit of a short fuse with her. So what about in their past? Sam seems to have achieved remarkable equanimity vis-à-vis her mother Phil. How did she get there? Will Sam go through empty-nest syndrome (big time)? She is so centered in her place of motherhood—in the first seasons wearing the “maman” nameplate necklace—it seems like the departure of all three girls from the house will bring about an enormous emptiness. Will it? In S02E02, “Rising", Sam leaves for the weekend—off for a girlfriends’ get-away to splash around at the home her friend Sunny’s uber rich boyfriend. Off in a private plane no less. Off to where a hired mariachi band greets the women when they arrive at Mark’s villa from the airport. Barely arrived though, Sam leaves. She gets Sanjay, one of the servants, to drive her away in a golf-cart escape and she goes to a modest seaside motel. Then Sam leaves again. We see her driving a black Dodge Challenger as picks up her girls, one by one, from their weekend babysitting places, and they all go the beach. A different get-away with her own girls (all of which we witness to the anthemic totem tune, Rising, by Corrina Repp.) But. Sam is still alone at the seaside motel. It’s been a fantasy. Where does Sam want to be? Let's talk about the acting Of all the girls, Max and Sam seem to have the most arch dynamic together. Is it because Max is full-on in hormonal teen time, or is there something in their relationship? Is all the tetchy stuff with the girls scripted or is any of it improvised? It sometimes sounds improvised, or seems so—especially with Max. Sometimes it looks like, Mikey Madison, the actor playing Max, is about to crack up. What were you looking for in the actors who auditioned for the roles of the three daughters? Where you looking for discrete traits as well as a traits that operated within the three as sisters and daughters together? Let's talk about the men How is Sam feeling about men? She says she’s sworn off them. Has she? Is she angry about men? Relatedly, was Sam negligent or a push-over in the separation settlement with her ex-husband Zander? Was she a push-over in the marriage? In fact, how did Sam even marry a guy like Zander in the first place? He seems so louche and flaccid and Sam is so full of fire and power. It’s very hard to imagine how that relationship ever happened. Relatedly, everyone in Sam’s immediate family—all female—have what our culture would deem to be male names: Sam, Max, Phil, Duke, Frankie. And Sam’s brother’s name is Marion, a name more conventionally thought of as female. What’s up with that? Ghosts What are your thoughts on ghosts? They make appearances across the seasons. And, more generally, what about energy? In Get Lit, S03E11, the episode starts with Duke and Phil clearing / smudging the house. In this same episode Sam’s father’s ghost appears. And in other episodes other ghosts appear too. There's S02E09, White Rock, where Duke sees the ghost of the dead woman. And in S04E10, Listen to the Roosters, Duke has a conversation with an old woman while seated on a bench near a food cart. At one point the woman proclaims to Duke that she can see the future. In the same conversation, and after Duke has said that she never wants to get married and have children, the old woman, who herself never married and never had children, talks to Duke about the role men played in her life, noting that they’d given her music, love, danger, ideas, adventure, all of which shaped her. But, as the woman says next, she’s preferred being alone and feeling good about being alone with herself. So, are men a distraction? Taking away from women who they are capable of being? The woman on the bench vanishes—another ghost? Or is Duke actually talking to her future self? It seems to be Duke who most intersects with otherworldly phenomenon. How did that come about in her life? And, Sam. A bit more on Sam. In S04E03, Sam walks in on Frankie who is in bed with a boy. Sam goes to talk to Max about it. Part of the conundrum for Sam is that Frankie is with a boy, and says so to Max, plaintively pointing out to Max that she said once that Frankie is a boy (S01E10), to which Max replies, “mom, I never said that”. It’s not true. But Sam doesn’t confront Max with that lie. How come? In fact, Sam demonstrates enormous largesse towards those who have fallen short. Sunny’s ex, Jeff, is a really great case in point—Sam extends and huge “OK, we mess up in certain realms” to Jeff post-divorce, and even when he messes up again (S02E07, Blackout). But Sam is still is pretty ballast about it—she’s not thrown. She simply see Jeff’s utter mess, which seems to liberate Sam even further. How has Sam achieved such balance? Such compassion? Is that what she has? Would Sam move to New Orleans? Is Sam a beast of LA? It seems very much her ecosystem. Could she live anywhere else? (Although, having been in New Orleans myself, and being someone chatty in the way that Sam is, it’s a great city for chatting people up, which is most definitely central to Sam’s ecosystem.) Episodes

Do you have a favorite episode? In re-watching the series, S02E09, White Rock, really struck me. It seems to be about legacy. Family legacy: those lost, those stolen (the Indigenous man in the museum exclaiming his family belongings should be returned); even legacies that linger at the edge of our lives—the ghost the Duke sees and then makes peace with.

What’s with all the rain in S04? Lastly. What are better things? Tonight, it's the Oscar's. I'm rooting for a few things, a few people. In anticipation of the night, I share the conversation points I would love to get into with Maggie Gyllenhaal, the writer and director of The Lost Daughter and whose film is nominated in three categories. (I'm rooting for her.) I found the film mesmerizing and as soon as I'd finished it I wrote down what most struck me. It came out in bullet-points, as questions I'd want to ask Gyllenhaal. I tidied that list up a bit, but it's still a bit elliptical, like someone snuck a list of questions into some paragraphs. This piece contains spoilers ... Leda is 48 and within her we still see her firm and fiery younger self—a self that surfaces full force in the flashbacks to Leda as a young woman, a mother, married, with two young daughters. Now Leda’s traveling alone and settled into an island village for an extended stay.

Within the first minutes of the film, Gyllenhaal gives us Leda’s body above the surface and below as she floats in the sea, paddles and stands in the water, watching what's around her; all 48 years of her in a bathing suit. In this way we understand two things about Leda: she has a body (which mothers distinctly understand from conception onwards) that engages with the world around her (swimming, dancing); and, she is a woman who is unapologetic in her solitude—at the beach, going to dinner, having drinks, at the cinema, alone. We also learn, more gradually, that Leda sets boundaries: she won't move from her beach chair when asked by the matriarch of a boisterous family overtaking the beach and wanting more room; she confronts the disruptive drunks at the theater; she asks Lyle to leave her to her meal at the restaurant; she won't let Will up to her flat to discuss the tryst plans he has with Nina; she leaves her husband and children. Leda wants things and pursues them in ways we’re conditioned to allow men to do, but not women. Maybe the most striking example is when, in flashback, we see Leda’s thesis advisor come to her dorm door at the academic conference they’re attending after her work was discussed in awed terms by another scholar in his address earlier that day. Now at her door, this advisor appears, humbled and a little bewildered, to ask Leda to join an invite-only dinner reserved for the conference rock-stars. Seated beside her stuffy advisor at the large table, Leda is bidden to join the more flamboyant academic who referenced her work earlier, and she re-seats herself with him and his rowdy pals at some distance from her advisor, relocating to the cutting edge, where all the fun is. Brazenly and unapologetically, Leda grabs onto the praise, going to where the high bar of new challenges and achievement reside. Women don't do this. Men do. Leda did. Leda is also complicated. And weird, and maybe even a little nuts. Is she? As a younger woman, there was a slightly unhinged vibe to her in that what-ignites-me-extinguishes-me kind of way. Now, older, Leda seems slightly more driven by grief than the drive that propelled her toward the independence she grabbed onto earlier in her life. Now, on this island, in a gesture she can’t explain and we may find hard to understand too, Leda surreptitiously steals from a little girl at the beach a doll like her own long ago—a doll that she gave to her young spirited daughter Bianca who marred it and that Leda then chucked out the window where it broke apart on the road below. Now Leda tends to this stolen doll, mothering the doll, cleaning her, preening her, buying her a new outfit; sleeping with her. This looks like grief to me. This looks like the crazy that grief can coax out of us. What is Nina’s attraction to Leda? Of course there's the defiance—Leda stands up to Nina's clan, that band of thugs she's married into. Is there more? Nina had to have trusted Leda an awful lot to openly acknowledge her sexual affair with Will, a betrayal that her husband, whacked on machismo, would surely punish brutally; in fact, Nina goes so far as to want Leda to collude in the orchestration of the next sexual betrayal by way of lending her and Will Leda’s apartment for a few afternoon hours. But Leda’s betrayal of Nina's daughter, stealing Elena's doll, is what crosses the line for Nina: it's okay for a woman to betray her husband, but not her child. Did Leda break the code of motherhood? After all, Leda found and returned Elena to her mother at the beach when the little girl had wandered off and no one could find her. Now Leda’s just stolen the girl’s doll. How did Leda think Nina would react when she confessed to stealing the doll? Any differently? And why didn't she lie? Why didn't she say she found the doll and cleaned her up to return to Elena? Who’s the lost daughter? As a mother myself, I think a lot about my own mother (from whom I surely learned some of how I mother) and what I feel most acutely is being a daughter who’s lost her mother (she died when I was barely a mother myself)—ultimately, leaving me the lost daughter. Is Leda a lost daughter? And we haven’t yet talked about the cinematography, which is sublime. Nor have we talked about the acting, particularly that of Olivia Coleman, which is equally sublime. Coleman’s performance strikes a remarkable balance of depth and levity, giving us a woman who is confident, capable, and possibly a little cuckoo too. Someone both clipped and compassionate, self-actualized and encumbered. Above all, Leda is defiant, and so is Maggie Gyllenhaal. When and where in contemporary culture is the silent consensus so blatantly broken open for us to watch a woman, a rotund one at that, eat an ice cream treat out in the open, lounging on a beach chair, her bathing suit visible though a gauzy beach dress, alone. I sometimes have restless nights and so stream CBC Radio One Vancouver because the time change lands me in the middle of excellent overnight programming. Last night was like that. As I slept and woke, and work and slept, I caught multiple hourly news reports broadcasting in real time the invasion of Ukraine. As the hours progressed, I listened to Margaret Evans reporting first from her downtown Kyiv hotel room to eventually reporting from an underground subway station that folks were using as improvised bunkers to evade the bombs exploding above them outside.

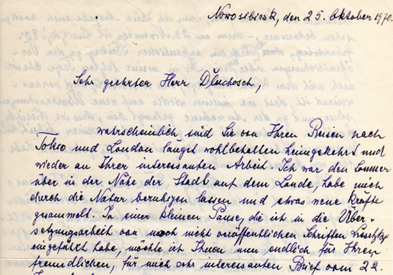

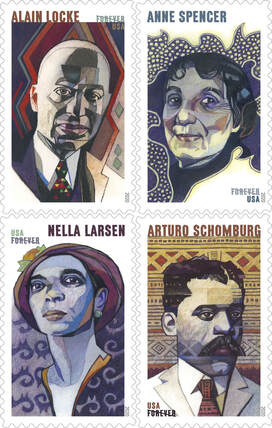

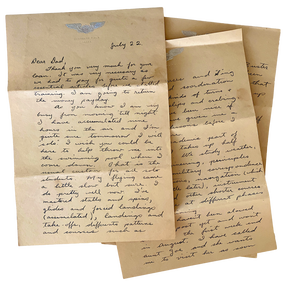

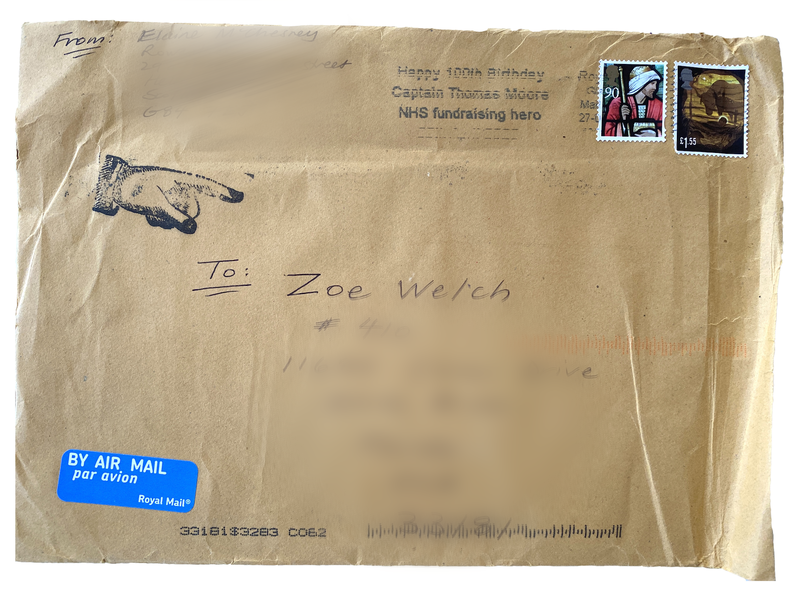

Listening to Evans’ steady voice, I kept thinking about the trucker-protesters here in Canada (and their inspired “compatriots” in New Zealand, Belgium, France, Finland, and the US), some of whom we heard in downtown Ottawa call for the execution of journalists because, they claimed without substantiation, journalists are in bed with government and are propagandists misleading the public with deliberate lies, etc. I didn’t hear a peep from any of the other protesters, nor their exuberant boosters, condemning such vile and violent calls to action. Nor did I hear a peep from them when journalists were spat at and screamed at with expletives, though not executed. This gaping silence was accompanied, in equal measure, with colossal hubris, otherwise known as a total lack of humility — the disingenuous swagger of self-righteousness. Journalists like Margaret Evans, and thousands more, go to work with helmets and flak jackets on. They wade into raging crowds to ask questions and discuss what’s happening. They don’t have body guards. They don’t arrive in armored vehicles – not in downtown Ottawa anyway. (Margaret Evens, though, might be climbing into one when she emerges from that subway station-turned bomb shelter). Part of a journalist’s job can involve putting themselves in harm’s way, even on domestic stories like the current one in Canada's capital city, a county that enjoys an international reputation of being “nice”. The least these protesters, their boosters, and their spectators at home can do is call out and unequivocally condemn the rallying cries to kill journalists, and condemn all other manner of violence visited upon them as they simply try to do their job. A job that might get them killed, even in Ottawa where bombs aren’t raining from the sky. So while Margaret Evens reports to us from a makeshift bomb shelter, the trucker freedom-fighters in Ottawa have installed a hot tub in the downtown of the nation's capital where some cavort in the hot frothy water while knocking back a few cold ones — it looks a lot less like they're fighting for their freedom a lot more like rocking their freedom to me.  February 14, 2022 Thirty years ago today I was blowing the smoke from my contraband Marlboro into the frigid night through the narrow opening between the window frame and its window, the cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other. I was visiting L in Charlottetown and we’d gone out to the country house that a friend of hers had lent us for a few days. I was on the mend from a recent break up, and still lingered in the territory we occupy after a loved one takes their life, in my case my father ten months earlier. Two days later I was back in Montreal and a day after that my son was at a sleep-over I’d planned so I could go see Primal Scream at Club Soda. But in the grips of loss I’d changed my mind and I was lying on my couch watching Thelma and Louise instead, letting my concert ticket go to waste. Part way through the movie, two police officers were at my door with the news. I let them in and they sat across from me, not far from the frozen movie frame paused on the tv screen. I didn’t want them to think I was shallow for watching this fugitive women caper commentary. It was before the internet and cell phones, so who knows how they found me. Police work. They were there to tell me that my mother had been found dead in her Vancouver apartment. Suicide. Valentine’s Day. I apologized to them for having to come out on a cold night to deliver such news to someone.  A decade later I was married for a time and Valentine’s Day was fraught for him, on behalf of me. Somewhere in the mid 2010s he thought we ought to embrace the day, in my Mom’s honour. And so started the tradition of going to a big hotel bar for a drink on each Valentine’s. Which is what I’m doing today. The 30th anniversary of her death. My mom lived with mental illness. Both my parents did. She raised me on her own, living on social assistance with the support of an exceptionally kind social worker. We lived in tiny one-bedroom apartments near Vancouver’s Kitsilano Beach (a fiscal hallucination now), me with the bedroom because she believed I needed privacy. She slept in the living room, first on a hideaway bed, and later, in a slightly bigger one-bedroom apartment, on a single bed pushed into a corner in the living room. When I moved out at 17 she moved into a bachelor apartment in a building for out-patients. There, we found another corner for her single bed, positioning it in such a way as to create a living area that felt separate from where she slept. On her birthdays I would offer to either clean her apartment (though she was pretty tidy) and make dinner, or take her out. She always chose out. Who wouldn’t. Sometimes we went to Vancouver’s Four Seasons Hotel lobby bar, or the one at Hotel Georgia. Of course we were way out of our price range, which was part of the fun.  The husband is long gone, but not my Valentine’s Day hotel bar tradition. My mom would love it. So would my father. (I eat a donut on his birthday because he loved going to his local Krispy Kreme in Miami where he chatted up everyone seated at the counter with their snacks.) I love this tradition. I feel so much closeness with my mom on this day, doing this thing. I can feel our silly thrill as I sit amidst the tonier well-to-do. Since 2011 when I became single again, I often invite a friend or two to join me on my tab. Until 2016 that was in Vancouver. From 2017-2021 I was in Miami for it. Today I’m doing it in Montreal — a first — and I’m on my own. For thirty years, I’ve been pretty quiet about my parents’ health, and even more so about their deaths. Close friends know. It’s a big thing to grapple with and I don’t want to freak anyone out. I’m fine (now), but strangers might not be. I’ve been especially quiet in my work environments. People are judgey — even if we're not supposed to be anymore — because, let's face it, diversity, equity, inclusion, and access hasn't exactly landed yet. This kind of disclosure carries a lot of heft and can carry even more innuendo. And so it concerns me that people will make assumptions and draw even worse conclusions. Not so much about my parents, but about me. I worry that people might ascribe to me whatever stereotypes they’ve acquiesced to — you know, shadowy, shameful stuff that can be weaponized to tank a career — taking away from me what they imagine my parents lacked. I worry that they can’t see past what characterized my parents’ deaths to see the resilience that characterized their lives. And mine. This was my mother’s greatest wariness. It dogged her. And so today, on this 30th anniversary, I honor my mother’s life, and her death. And, I honor every minute in-between. In public. I wrote an ode to my Mom on another Mother's Day. You can read that one here.  (For E. a letter-writer.) Don’t you want to pick that up? Turn the sheet over in your hands, hold it up to the light and see the glow through the page, feel the texture of the ink on the paper, sense the sender and the sendee, feel yourself carried through time to where this was, almost becoming the script, the scribe, and the go-between. I want to.  It looks like it's written on onionskin paper—a virtually sheer sheet, its lightness important during the days when airmail (called Par Avion at its inception in London in 1929) was costly and people economized on postage by using lightweight paper. I don’t know if I would be as inclined to want to handle and explore this letter if it were typewritten, to let it linger in my hands, its physicality the thing transmitting the fullness of its metaphysical dimensions. I might still want to read it as eagerly, but with so much sensorial promise gone, much of the personal would be too. Letter-writing gets short shrift these days, considered a relic at best, a waste of time at worst; it’s gone from something quintessential to something antiquated, something once consequential to something now condescended to—mostly. Retro is currently cool in culture – vinyl records (even reel-to-reel); 35mm cameras and Polaroids; rock band t-shirts; high-waisted pants; cocktails and shaker kits; even IG filtres – but letter-writing hasn’t made the cut. There’s not much to package and sell to the practitioners of longhand. Maybe that’s why. Lives are recorded in letters. And the life around those lives laces the written lines, forming cultural records that capture and reflect for us the more intimate portions of collective life as they play out in private spaces. Why else would letters like the one above join collections in public archives, libraries, and museums? Letters contribute to our public history. If you type “letters” into Harvard library’s special collections search engine, and then “image”, you get 9,655 hits. If you do the same for the New York Public Library you get 18,038. What will happen 20 years from now, and 50, and beyond that? Will we publish emails? Not likely. Most of us delete our emails, and few of us turn to the mode with the tenderness, time, and tenacity it takes to correspond by letter. And we’d have to pass along our passwords to someone so that our emails could eventually be retrieved. Who do you share your passwords with? In any case, when’s the last time you lingered over an email—made a pot of tea, and settled into a comfy chair to read, and reread an email? Some don’t even use email anymore, or never really have, it too relegated to a generational joke. You know what I mean. I recently described to a millennial the functional hiccup I encountered on a website, and she suggested that it was probably because I’m “old” (she used air quotes), rather than considering for a moment that the platform and its navigation might be poorly designed and/or have had a glitch. It took everything in me to not roll my eyes and tell her that I’ve been using computers for longer than she’s been alive; that, apparently, though the web may be wide, her use of it as a conduit to the world seems to be pretty narrow, and narrowing. Ask Nick Cave about the power of a letter. No, wait, don’t—instead, listen to his 2001 ballad, Love Letter, an incarnation of the plaintive ache his composition is meant to remedy: Love Letter, love letter / Go get her, go get her / Love Letter, love letter / Go tell her, go tell her. What more is there to know about the potency of a letter? For the curious, the kindred, and the quixotic, letters also come bound and published as collections. I’ve read the collected correspondence between Al Purdy and Margaret Laurence, and between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz; next on my list is the published collection between Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark as well as the letters of Earnest Hemingway. I’m a letter-writer, which you’ve probably already figured out. I have a long history with letter-writing as well. My practice has always been the long letter, long in time to write which yields a letter long in pages. I’ll write over the course of a month or so. By the time I wrap it up, my sendee has accompanied me along multiple storylines in my life, the letter taking on narrative momentum a bit like a script might, but without the formal constraints of the three-act structure, resembling something more akin to Richard Linklater’s 2014 film, Boyhood, another manifestation of the filmmaker’s question: how do we cope with time passing? (Some letters help track what might offer answers to that question, or at least shed some light.) A storyline of mine, in a letter, might come to its conclusion within the span of the letter, or in the next one. Andrei Tarkovsky, another filmmaker whose work has expanded filmic language, wrote about his work and his aims as an artist in Sculpting in Time, describing film’s particular capacity to express the course of time within the frame. Letters do that too. I’m also into stamps, though I’m not a stamp collector. I always look forward to renewing my stash of stamps, making my selection based on the artistry and the message, little pieces of art I then send across the world. Right now I have round ones with chrysanthemums for international postage (there’s not a wide selection for international), a set of Voices of the Harlem Renaissance for domestic, and a set of coral reefs for postcards. It’s amazing how much there is to choose from—something to suit a range of tastes and interests. Do you remember Fargo? (The Coen brothers' film, not the series.) In it, running on a very minor plotline, Police Chief Marge Gunderson’s husband, Norm, is working on a painting for his submission to the federal duck stamp contest. It’s a thing. (Norm’s mallard earns him second place on the 3-cent stamp, a disappointment to be sure. No one uses the 3-cent stamp, he tells Marge. Of course they do, she replies, ever the pragmatic optimist and loving wife, whenever they raise the postage, people need the little stamps.) The duck stamp contest was started by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 as part of a conservation effort to protect wetlands and wildlife habitat, and it continues today. Conservationists buy duck stamps, knowing that 98% of the cost goes directly to protection work. Stamp collectors buy them to help increase their value, thereby increasing the returns to the intended conservation work. My first letters were written to my parents. To my father who lived far away from me as I grew up, and then to my mom, once I moved away from home. I love my father’s handwriting. It carries the same verve as the poems he wrote. I love my mother’s handwriting too. Once we began corresponding regularly I noticed that the W of my signature was very much like hers—a graceful line elongating the arc of the final curve. Over time I noticed how the way I wrote all of my last name had almost completely taken on the shape of hers—the looping lines drawing out the direct link of my lineage. To this day, I think of her each time I sign something by hand. And whenever I open the box where I keep the collection of our letters and cards to each other, our bond is illustrated in the assemblage of envelopes addressed to and from the same name, in the same script. After each of my parents died, I travelled to their cities to handle arrangements. This included going through their belongings, a strange and singular experience that mixes the past with the present, leading us to sometimes stumble onto secrets that might make sense of partial memories, and of family lore, helping to solidify one’s place and history, or at least to help illuminate it. My parents separated when I was an infant, yet I found letters between them dating from their separation to the time of their deaths. They wrote to each other as my parents, discussing me as I was growing through the stages of my life; and they wrote to each other as friends, across so much time and distance, and the troubles they each had. I found letters other people had written to them. And I found letters I’d written them. They’d each kept the letters.  Piecing everything together, I pieced together parts of my life I’d forgotten, with others I’d never known—some telling about me, some telling about the times. In it all, I learned more about myself, about them, and about their worlds. My mom wrote about the founding of Greenpeace, which was around the corner from us on W. 4th in Vancouver, and was where she volunteered. My father wrote about Mickey Munday, Miami’s Cocaine Cowboy pilot who lived down the street. And in a letter from my father to his, written when he 16 and in his first months of pilot training, I see in my father's maturing script hints of a  sterner man in my grandfather than any family story has ever told. It was the early 40s at the Randolph airfield in Texas and my father's attempt to fly for the air force an act of love on the part of a son for his father, an esteemed WWI pilot. The letter is written before my father failed pilot training. When I returned to Montreal from Miami where I’d gone to attend my father’s memorial, a postcard from him arrived in the mail. Postcards are often slower to make their way through the postal system, so it’s hard to know how close to his death he was when he wrote that card and mailed it to me. Included in the things I brought back with me from Miami was his suicide note, it in the same handwriting that swept across the postcard. I still have both.  Right now, I owe E. a letter. We’ve maintained our friendship through letters for longer than we’ve been friends in the same city. Occasionally we intersperse our correspondence with phone calls, and the rare text message, but it’s mostly our letters that hold us close. We send all kinds of things to each other in our letters. My last letter included several How-To Haiku zines I made so that E. and her Glaswegian pals could have a haiku-writing party together. Her most recent letter to me included a page torn from a small Muscat de Rivesaltes notepad, which I use as a bookmark (yes, I read physical books too ) and which I know she sent because she knows I love Muscat—it’s her promise to me that when we’re together next, we’ll go to her house in France where we’ll drink Muscat in the garden. Her letter also contained a little drawing illustrating something she was trying to describe to me about the nature of time. The illustration depicts E.’s woven Kabyle tray on the table beside her, it illustrating her point about time. There’s also the envelope, with its acknowledgement of Captain Sir Thomas Moore, the centenarian who started walking laps in his garden on April 6 to raise money for the UK’s National Health Service efforts to confront COVID (by the end of the day on April 30 – his birthday – his efforts yielded £32.79 million). And, finally, the Par Avion sticker there to remind us that this thing is not travelling to me by boat. Since the COVID lockdown, I also received a thank-you card from Our Community Bikes, one of my favorite not-for-profits in Vancouver. Working under the pressures this lockdown has caused so many, they held a fundraising campaign to which I contributed. They sent me this handwritten  thank-you card, mailed inside a hand-addressed envelope. No Avery type-printed address stickers for Our Community Bikes, and so none for me. For a while I was pen-pals with a woman in a Los Angeles maximum security prison. She was the mother of three, and was in under the 1994 three-strikes-you’re-out law. Her infractions were minor drug-related charges and traffic stops gone wrong. She was doing life.  For a few years in my early 20s I had a PO box at the main post office in downtown Vancouver, even though I had home addresses everywhere I lived at the time. (I once gave my PO Box address to a guy who asked for my phone number, telling him, cryptically, it was the best way to reach me, no matter what.) I loved picking up mail late at night, entering the quiet alcove of the post office, eyeing the others doing the same. Did they too have street addresses like me? I fell in love once through letters. We met at a conference in Banff, and then discovered that we lived 2,300 miles apart. And so when we each returned to where we lived, he to his small house on the Anzac reserve in northern Alberta and me to my brownstone walkup on the Montreal plateau, our courtship began by letter. He wrote in pencil, he explained in his first letter, because it’s more forgiving. And with that I was hooked. I once wrote a letter to my sister in New Zealand, and was so keen to be close to her that I photographed the pages and emailed them to her. And once, I wrote a letter to E. in Scotland, and photographed the pages to keep for myself, printing them out and pasting them into my writing journal to mine for ideas later. Years ago, in the wake of my parents’ deaths, I wrote often to L., my closest friend far away, who later told me and tells me still: I have all your letters. When you’re ready, they’re yours. I haven’t asked for them yet. Today, I’m a museum educator and I work a lot with senior high school students. No matter the project, I ask them to explore their ideas with a pen and paper because the brain behaves differently that way. When writing longhand, neural activity is triggered in particular ways—all good for cognition and creating. The field of research known as “haptics,” which includes the interactions of touch, hand movements, and brain function, tells us that cursive writing helps train the brain to integrate visual and tactile information, and fine motor dexterity. So, it’s spatial, cognitive, and kinetic. Other research highlights the hand's unique relationship with the brain when it comes to composing thoughts and ideas: a material activity, and slower than typing, handwriting forces us to rephrase ideas and concepts in our own words. So when I ask students to write by hand, they’re making sense of their learning, and their world, in their own voice. Additionally, the process of production that handwriting involves, each letter formed component stroke by component stroke, recruits neural pathways in the brain that go near and through parts that manage emotion. All this making learning both stickier and more holistic. These benefits are aren’t just for young brains. Neuroplasticity belongs to us all. We each have the capacity to continually change our brain’s architecture and operating system (neurons that fire together wire together). And it’s not just writing longhand that enhances positive neural rewiring—reading longhand does too. When we read handwriting, we activate the same neurological instructions required to write those same letters and words, something keyboard-written type doesn’t demand of us. So, basically, to read handwriting is to be empathetic. There’s also a heap of research on attention: how much, how long, and how deep our attention is when we read online versus reading something in our hands. It turns out that deep reading – the process of thoughtful and deliberate reading through which we actively work to critically contemplate, understand, and ultimately enjoy a text – is compromised when we read on a screen. When we skim and scan a lot, and surf from hyperlink to hyperlink, our brains get good at skimming and scanning and surfing – to the brain, all shallow activities – and less good at neurological deep diving, the kind of brain capacity required for concentration, contemplation, and reflection. So, as we reroute our neural pathways online, we are remaking ourselves in the image of the internet—the medium is indeed the message. I remember a day in 1996 when I gazed for a long time at one of the first advertisements for a wireless phone. The billboard presented the image of a pristine conifer forest, sunrays filtering through the grove of trees, with the words finally free plastered across the tree tops and reaching into the sky--two little words redefining the concept of being untethered (just two of the many that have grown into the barrage of lexiconic gaslighting we have today). Alternate facts, indeed. These days, more than 20 years since that ad came out, in an attempt to simultaneously unplug and reconnect, people now pay to attend forest bathing workshops in groups that are led by somebody who asks that phones be turned off.

There are tangible costs and consequences to those today who choose to opt out or who limit their participation in the online world. From being mocked and called a Luddite (go read about the Luddites, they’re pretty interesting), because, apparently, it’s unchill to step away from monolithic click-bait corporations instead of capitulating to the transactional interests of their opaque business models (like FB [uber uncool] and its millennial-pacification do-over, IG); to more culturally ubiquitous and coercive expectations, silent and tacit, that you must migrate your life online to work in today’s economy (think LinkedIn), even if your work takes place off-line. It’s not called the attention economy for nothing. I don’t want to go fast and break things. I don’t want to lean in. I don't want to curate my life, and pin it. I don't want to follow influencers. I don’t want to read Toni Morrison on a backlit screen. I don’t want to use performative platforms to maintain my powerful friendships, especially when a long stretch of Earth keeps from us being together in person. I don’t want market-driven algorithms driving my information, my attention, and me. I’m not a consumer of content, I’m a sentient being, animated by caring, curiosity, and concerns of all kinds. I’m not a content creator (a stunning piece of language that so baldly reveals the vacuity of the enterprise), cranking out filler for the spaces between the ads. I’m an artist. I’m an agent. A citizen. I choose analogue channels. I choose digital channels. I choose. I wonder about those who don’t write by hand anymore, and those who don’t correspond by letter. In a world absent of handwriting, and where no one writes letters anymore, there’s an empty mailbox, an empty archive, and what more? It would seem there’s a lot to lose when we put down the pen. We lose connection, we lose our unique dimensionality, it looks like we're going to lose pieces of our histories both personal and public, and, apparently, we’re losing our minds. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees. Maybe experiencing forests by paying someone who first tells you to turn off your phone while you’re there is a good sign that there’s a system glitch, a big one. I’ll check the mail later. I always know when it arrives. The postman on this route talks on the phone all the time. He has on a headset but he’s loud. I can even hear him when he’s driving up and down the street, his cheerful holler blasting from the open truck doors. But for the moment, I’m going to go inside and type this up. (You knew I was writing this by hand, didn’t you?) I wish there was a way for your read it as it is. Not this time. PS: I was prompted to write this essay for work. While the museum remains closed, we’re all pitching in to produce virtual experiences, including writing pieces for the blog. With the threat to the US Postal Service on my mind, I offered to write something about letters. Writing on commission is unusual for me. I loved working with a gifted editor, and was interested to see how and where my personal voice had to conform to an identity other than my own. Here's the version of this piece that went up on the museum’s blog. It’s pretty different. (And, no surprise, the blog version is a lot shorter—I was told that people just don’t want to read anything too long. So, the dictates of the medium do indeed dictate the message.) resolve

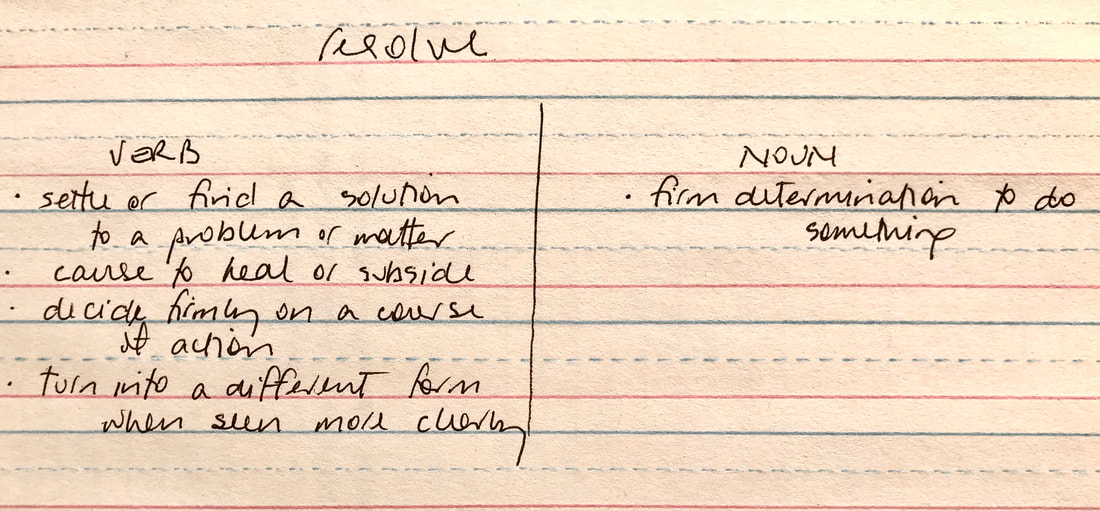

That’s my word for 2020. For over a decade, on December 31 I’ve made it a practice to choose word for the coming year. I’ve lapsed a few times, “life” derailing things. But, I have a word for 2020 and it’s RESOLVE. I came upon the word this way: Yesterday morning, I was doing some writing, the freeform kind that always settles my brain, the kind where I feel my neurotransmitters settling as they organize into something probably akin to what is called a meditative state, where I feel enter something I know I can trust. I know this thing. It has no name. As I wrote I found my way back to a story Laura (an artist, friend, and former business partner) told me some years ago. When in art school, Laura had a professor, she recounted, who remarked on a piece she was working on—he told her it was unresolved. She explained, and the concept stayed with me. Unresolved. Resolved. Something that has brought itself to its conclusion. That has tied up the loose ends. That has achieved its intended outcome. That has achieved perhaps not what it set out to do, but what it was intended to do. This implies a tension between what we set out to do and what is set out for us to do. And I’m uncomfortable with the implications. I’m not exactly certain what “it“ is that would have us “do” something this way and really not that way; yet, I’ve lived long enough now, and jumped into enough unknowns—deciding this to do and not that, to go there and not stay here—that I have to acknowledge something resembling a grander sense enjoins itself, in ways unbidden, to endeavours. I probably wouldn’t ever be caught asserting that it’s something as grandiose as a path—there are just too many paths out there for there to be only one—but I would definitely bank on there being something that introduces meaning, or at least invites meaning to the table. And so, as I enter and embrace 2020, I invite meaning to the table. A cross between an artist, an adventurer, and a detective, I embrace boring into what is before me, pulling on what’s passed, on intentions both lagging and wagging, to achieve work through catch and release. Because as any artist worth their salt can attest to, creating is an alchemy. It’s a tug, a tension, a balance. It’s holding on and letting go. We hold on to what we mean, to what we set out to achieve, to what we intend for ourselves and for our work, while also realizing, and (importantly, whether we know it or not) relying upon our letting go and allowing another force to enter into the process. And when we do, as any artist must confess, the work is better. It finds its purpose. It achieves resolve. We have worked with what we know and what we want and what we want to do, and we have acquiesced and danced with the unknown, understanding and cultivating all that the unknown brings with a kind of faith that is uncanny, and indispensable. So, for 2020, I declare for myself resolve. Which is to say, I embrace this year, this life I have, so that I bring to it a state that brings it to its outcome, honouring my intentions with those that make themselves known along the way. It’s not for the faint of heart. It is the work of an artist. And it just so happens, as I’ve come to understand it in these past days nesting alone, that my work in 2020 is both the tableau and the table. May I achieve resolve. May you join where you can. When my mom was still alive and when I hadn't yet left Vancouver—a very, very long time ago—we saw the Cy Twombly show at the VAG when it was still in its location further down Georgia Street. My mom with mental illness roiling around inside of her looked at the works and said, this makes me feel anxious. We left.

It was completely liberating for me. All these years later, I allow my instincts to animate me: I either breeze by pieces or, riveted, I root in front of them, moving in so close to see their inner workings that security often thinks I’m touching and edges closer to me to keep on eye on my activity. Every time I’m in an art space, just like today as I wend my way through this sprawling survey of Sterling Ruby, I think of that day with my mom so long ago. I've crouched in a corner hiding from an imaginary shooter twice in my life.

The first time was when my son was 10. We went to a birthday party for one of his friends that included playing laser tag at a local outfit. There, strapped into a bleeping vest, I ran through the black maze in the dark trying to dodge everyone else in their bleeping vests, and I was terrified. The experience of feeling stalked, even by a 10 year old holding a play gun that emits beams of light, was so traumatizing that I found a corner where I crouched, knees up in front my vest to hide its blinking lights, hoping nobody would find me while I waited for the game to end. The next time I crouched in a corner to hide from a shooter was not voluntary. I lead a museum program that takes me into ten senior high schools in Miami-Dade County each year. I'm currently winding things down for this edition and am visiting the classrooms for our feedback sessions. This afternoon, I happened to be in a school when a Code Red drill started. This is when students and teachers put into action the training they've been given in the case of an active shooter at their school. From one instant to the next, a calm conversation with the kids was blasted by a loud buzzer and suddenly the teacher was up and crossing the classroom floor to turn off the lights, lock the classroom door, and close the blinds that give onto the hallway. Simultaneously the students moved en masse into a corner of the classroom away from the door and windows where they crouched under desks. I had no idea what was going on so I did the same thing: I hunched under a desk alongside 20 students and their teacher. I asked the 17-year old girl beside me what was happening and she whispered back, a Code Red practice, and then had to explain to me what that meant. (I moved to Miami from Canada and am still learning about this place.) Glancing around me from there under that desk, I noticed several of the juniors were wearing what were clearly school-issued t-shirts with the caption, Graduation Class 2020. And there, hiding in a dark corner with all these kids, as I stared at their shirts in the long shadow of the Parkland school shooting just a year ago, all I could think to myself was, not at this rate. (Started just over two years ago and then put away until a few weeks ago, I finished this today. For my witnesses.) You are that guy now

|

authorzoe welch Categories

All

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed